Spending time as I do in the Blue Ridge Mountains offers a great opportunity to commune with the beauty of nature. However, where I stay, being at the end of a serpentine dirt road snaking its way deep into the forest, affords a level of social connection just north of Neil Armstrong’s solitary stroll on the moon. Jeremiah Johnson I am not. So to break the spell of the woods, I often go in search of stories. The other day my friend Eddie, mentions a local restoration specialist. Game on.

Escaping from my forest sanctuary, I head out to meet a man who I would come to respect as an artisan. He works in the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains where he produces Amelia Island, Pebble Beach and Cavallino quality work with a special place in his heart for British cars.

Meet Mike Gassman.

Woulda, Shoulda, Coulda with One of America’s Most Important Cars

1907 Thomas Flyer

Heading north, the Rockfish Valley Turnpike passes beneath the terminus of the Virginia Skyline and the entrance to the Blue Ridge Parkway. We are talking God’s country. Clinging to the western side of the mountain above the Shenandoah Valley this old blue highway cuts through the Rockfish Gap before descending to the valley floor below where my destination awaits.

Clean and white with a garnish of distressed old British sports cars from the 50s and 60s dressing the side lot of the shop, Gassman Automotive presents itself as a buttoned downed source of high end restoration services, NOS parts and restored vehicles for sale.

Mike Gassman welcomes me with the warm humor of an old friend. In his mid-50s, he possesses a forthright country geniality reflecting his farm family upbringing. Mike converses with the intensity of a high energy, engaging storyteller. Conversations reflect the technical acumen of a master restorer delivered with the flavor of comedian Ron White.

Time spent at Gassman Automotive offers rich servings of eye candy and good information. Mike’s business offers a great story. However, that story will have to wait to be told another day. Why? Because before I interviewed Mike he told a couple of great stories that I had to share, now.

As we walked through his fabrication shop, Mike motioned to a bare metal shell mounted on a rotisserie. It appeared to be a smaller mid-century coupe of European breeding. Indeed, it turned out to be an early 1960s AC Greyhound. It actually represented a very rare find considering the total production numbered just 83 with only three having left-hand drive with this being one of the three.

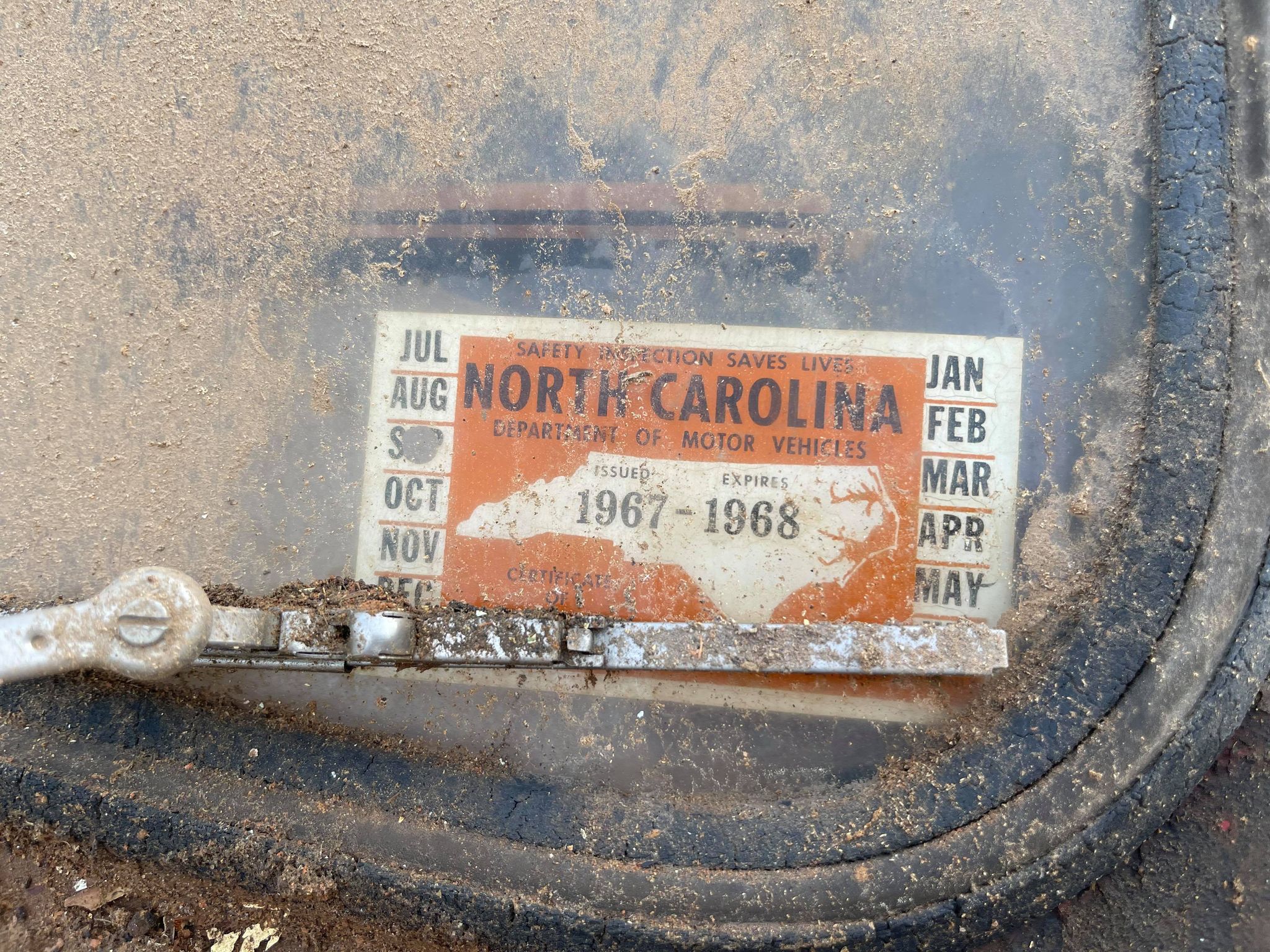

It had been off the road since 1968 and left untouched in a barn in North Carolina. It would spend the next year undergoing a full restoration at Gassman. As Mike told it, the really funny part of the story resided in the fact that it had sat quietly for over fifty years under a thick layer of dust in a barn within sight of Tom Cotter’s home. Yes, that Tom Cotter “The barn find hunter.” As Cotter says, “They are out there, sometimes right under your nose.” Cotter must have laughed at this find.

With that story told and well received, it triggered Mike to bust out saying, “If you like barn find stories I have got one for you.” As told to me by Mike, it actually starts well before Mike was born in 1964.

Mike says, “My family ran a dairy farm in Alden, NY east of Buffalo. A widow lived on the farm next to ours.” Apparently the widow’s deceased husband had been good friends with Mike’s grandfather, so Mike’s father would farm her field for her. Before Mike’s birth his dad had a real thing for brass era cars. Mike says he heard his dad probably had 20 of them at one time. In the course of tending the widow’s farm Mike’s dad discovered her barn contained a terribly distressed but very interesting car from the brass era. Mike’s dad had his eye on it with intentions to buy. With that in mind Mike’s dad would take every opportunity to squirt a little oil in the cylinders and turn the engine.

At that time Mike’s dad supplemented his income of $45 a month from farming with money he could make flipping cars. Mike says, “He would buy a car for $5 get it running and sell it.” Though the widow’s car was in terrible shape she wanted $500. Mike’s dad felt the $500 price outrageously steep especially considering its condition.

Mike says, “I have heard this story a million times. One day in the 1950s as my dad rides over to the widow’s farm he sees a tractor-trailer backing its stainless steel trailer up to the barn. On the side it reads “Harrah’s.” Ken Gross writing in Hagerty/Insider quotes David Gooding recalling Harrah’s trucks saying, “There were semi-trailer trucks bringing cars that they’d picked up around the country, every few days – both cars that were pulled out of barns and new purchases. They had different car spotters in different parts of the country.”

While Mike’s dad had made offers for the car, they never approached the $500 asking price. He accepted the reality and helped load the car onto the truck. He watched the loading of two straw filled crates that contained the vehicle’s brass head lamps. Lastly he witnessed the loading of what would prove to be a very important old bicycle. And that, was that, until.

Over a half century later young Mike, born in 1964, had grown into a master restorer fine classic automobiles. In 2008 he had brought one of his restorations to the Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance. On the day of the judging, in the early morning hours, he went to the underground garage where cars had been stored to detail his car. Right next to his entry stood the car that he recognized as the “wreck” his father recalled pushing onto Harrah’s trailer.

Michael knew more details than most about the 1907 Thomas Flyer that had won the 1908 “New York to Paris Great Race” and its grand prize of $1,000. (An interesting sidebar to history is that, at the time, the race sponsors The New York Times neglected to present the prize money to the winning Thomas Flyer team. It would be another 60-years, in 1968, that The Times awarded the money to driver George Schuster the only team member still alive.)

Michael knew that the Thomas Flyer finished first in 169 days beating the German Protos in second place by 26 Days. He also knew the significance of the headlights and the bicycle.

While the German entry, the Protos, had arrived first to Paris, the Germans had been penalized for cheating (The Germans had put their car on a train between Ogden, Utah and San Francisco) so the American had the race in hand until a gendarme refused them access to Paris and victory. Why? Parisian law required two headlights and the Thomas Flyer only had one. Unfortunately the Thomas flyers lost a headlight during a misadventures along the route. Just as things seemed poised on a pin head and ready to tilt towards ugly, a gentleman offered the team his bicycle which had a carbide lamp. After numerous failed attempts to attach the headlight, the team simply lifted the bicycle onto the hood of the car and held it there by hand allowing the Thomas Flyer to enter Paris and claim victory.

Now standing next to the Thomas Flyer he just stared as a man came over and began wiping the car down. Mike says, “I told the guy, my dad had a chance to buy this car in 1952 for $500. He looked at me like I was an idiot. I said believe it or not. He said I find it hard to believe.” The man then asked Mike where his dad lived and Mike said Alden, NY. Mike says, “His eyes lit up.” Mike then told him that his dad had pushed the bicycle next to it and carried the two crates with the headlights into the Harrah’s truck. Mike says, “Now the guy was listening. That I knew about the bicycle flipped him out. I learned later that day that he was the grandson of Ernie Schuster who drove the Thomas Flyer in the Great Race.” Mike says, “If you ever want to read a great book about it all get a copy of Race of the Century by Julie Fenster”

Today, the 1907 Thomas Flyer that won the 1908 New York to Paris Great Race has been recognized for its historic importance by its inclusion in The National Historic Vehicle Registry. It now resides in the pantheon of most significant cars in American automobile history, treasured by the National Auto Museum where it resides and a priceless icon, which, Mike acknowledges, his dad passed on for $500.

Glad to know I’m not the only one who’s “passed” on what would become future treasures. I’ve got a BMW 507 story……..

I would certainly like to hear your story one day.

Great story👍

Thank you for your kind comment.