Conversations With People We Value #25

It would be my first job in the automobile industry. It was 1975 and Mercedes-Benz of North America hired me to create their first audio-visual technical training system. I would be creating educational programs to train technicians at the dealership. I was thrilled to be working for the iconic three-pointed star – A good company, with good people and great cars. I had no clue that I stood on the brink of what would be a lifetime avocation.

It happened so serendipitously. One day early in my career at Mercedes-Benz I encountered the very polished Count, yes Count, Marcus Clary a Public Relations executive. He was discarding new car brochures from previous years. I asked if I could take some. Help yourself was the reply.

Thus began a lifetime of opportunistic dumpster diving at North American car companies as decade after decade I witnessed most automotive manufacturers indiscriminately discarding what they viewed as outdated sales literature and I saw as important future messengers of history.

Over 100 years ago the new car brochure came to life in a world cluttered with expensive hand built cars desperately seeking to be noticed.

Over coming decades the new car brochure would evolve as a powerful 20th century sales tool and a valuable reference for the future study of automotive history.

Now as we witness, with some sadness, the sacrifice on the altar of digital efficiency of the high quality, brilliantly photographed, aesthetically striking and increasingly expensive bibles of the new car sales effort, I would like to take an admiring look back at whence they came.

Evolution of the new car brochure

(Part 1 – 1900 to 1940)

1936 Ford

In the early 1900s the emergence of the automobile as a commercial venture demanded printed material that would help present, position and promote this new contraption.

Over roughly the next one hundred years the new car brochure would tide a wave of evolution and sometimes revolution in design, technology, socioeconomic conditions, societal values, editorial style and graphic delivery.

One need look no further than the very first page of the very first Cadillac catalog to see the role set aside for the new car brochure. The year was 1903.

1903 Cadillac

“Being unable to reach the majority of prospective purchasers of automobiles by Agencies or personal calls we hand you this catalogue which, in a measure, gives a knowledge of the Cadillac and its most important features and at the same time illustrates and explains the vital points so that comparisons may be made with other vehicles and thus enable you to satisfy yourself as to our claims for superiority over all others.”

Granted while that explanation makes for one hell of a sentence, buried within that mouthful of wordy formal prose resides the essence of the new car brochure for the next 100 years. Its purpose was established as a means to “provide a tool to engage, inform and persuade prospects to purchase the product.” Its progress would be marked by increasingly higher quality materials, idealized imagery and persuasive copy integrated ever more professionally to motivate a new car prospect to be a new car buyer.

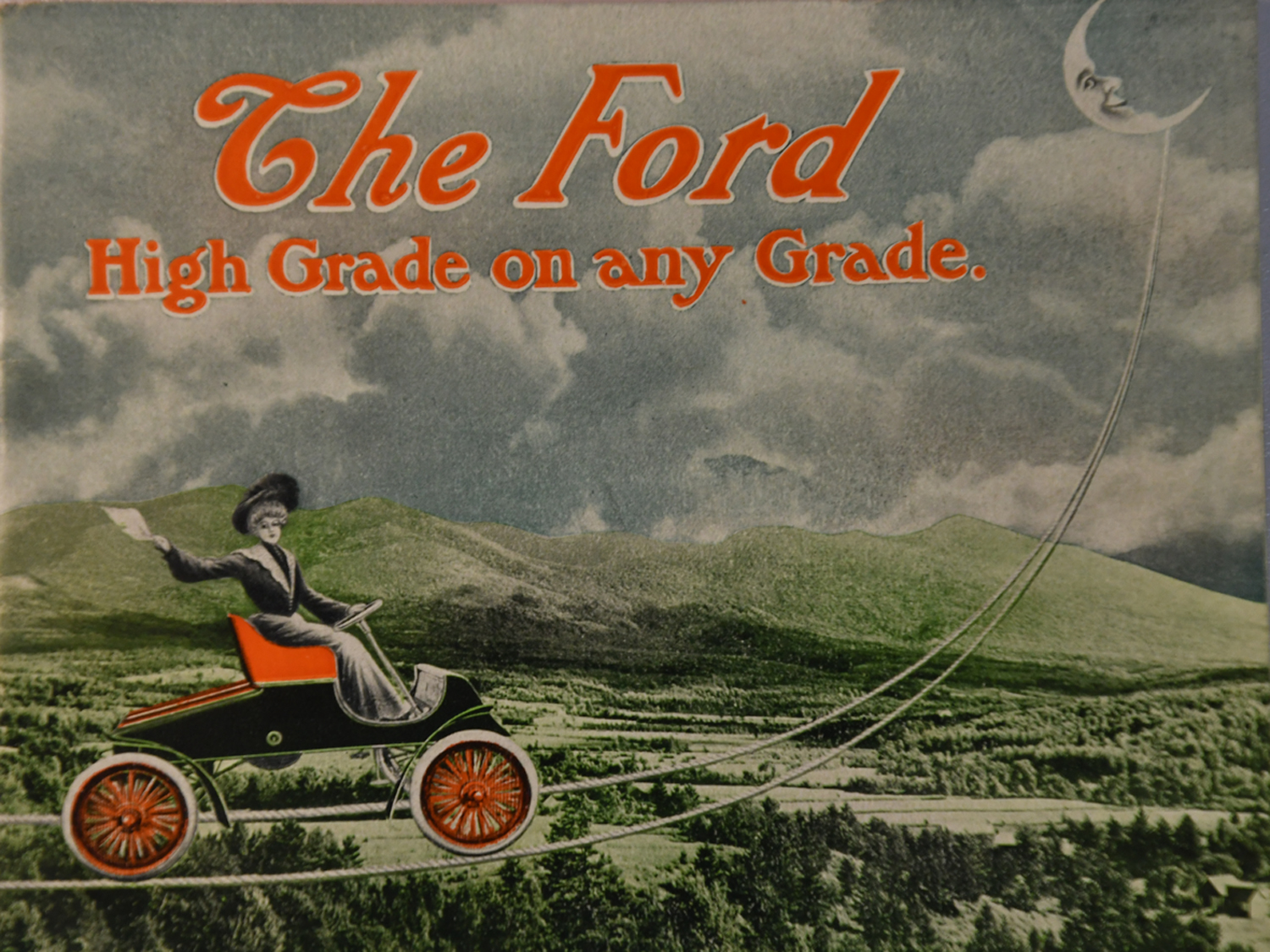

1903 Ford

It would do so, in part, with an emotional appeal that paired the purchase of a new automobile with a romantic vision of the real life experience that that automobile would deliver.

When the automobile arrived on the popular scene in the 1900s, it cost an average of $2000 to $3000 and up at a time when the typical American worker made around $500 a year.

In this early age of motoring most everything associated with the automobile, its operation and its value was an unknown. Skeptics abounded. Many viewed automobiles as the rich man’s toy and a passing fad. This skepticism posed a daunting challenge for those tasked with writing persuasive copy for the print automobile brochure. The challenge posed demanded that the early new car brochure advance a strongly substantiated value proposition to an often dubious populous dismissive of this new mode of autonomous mobility.

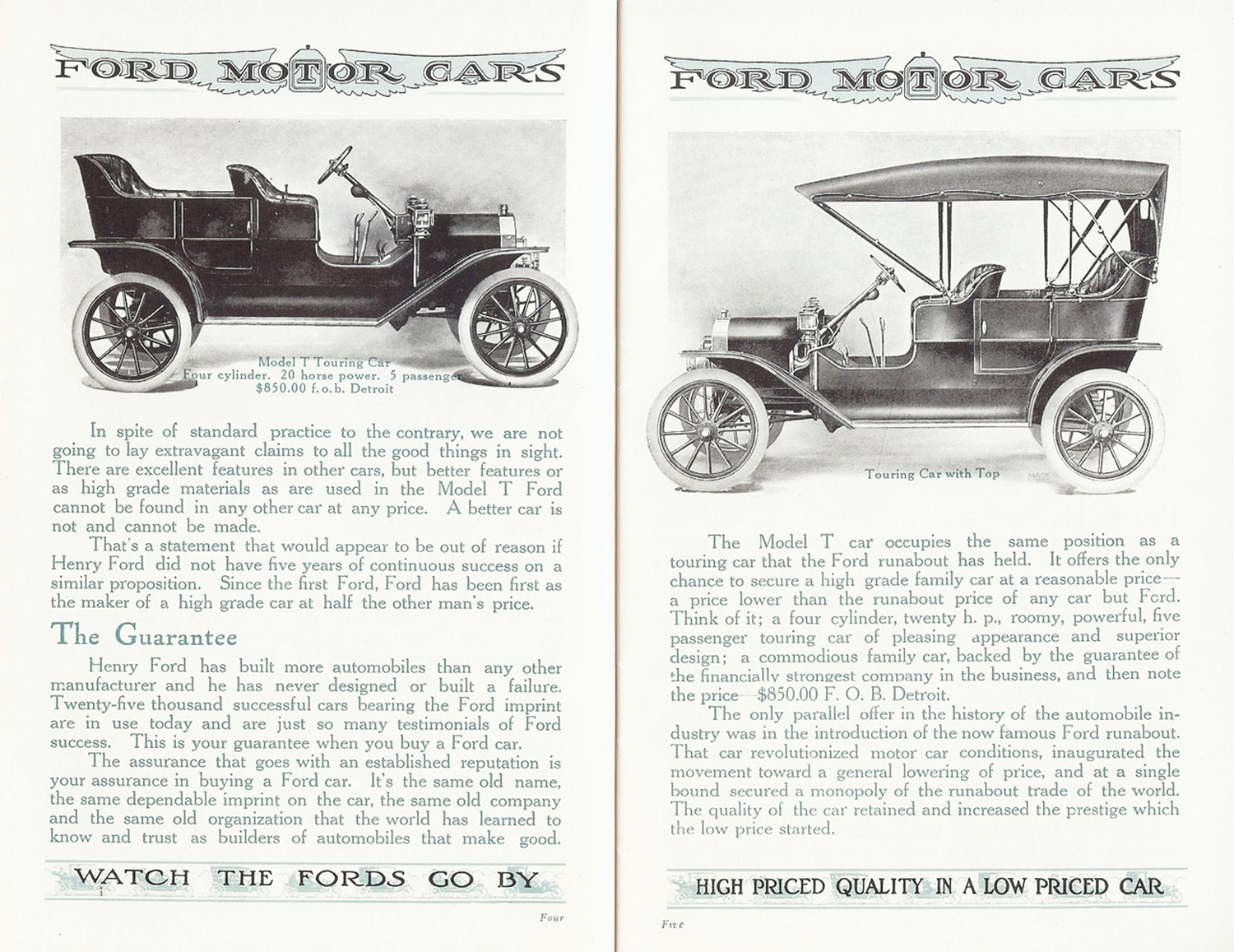

1909 Ford

Early new car brochures displayed the work of journeymen graphic designers whose names have been lost to history. Brochure content displayed a visually staid countenance featuring a forthright presentation of product and corporate stability.

1906 Cadillac Factory

An image of an imposing factory was often a prominent feature to assure a wavering prospect that this manufacturer was stable, substantive and here to stay. Even then, the very concept of and need for the automobile required explanation.

Designs featured basic type with custom hand drawn fonts for graphic interest. Art was predominantly illustration. Color was used sparingly, Image reproduction employed the recently available half-tone technique. From this basic beginning would evolve a century of ever improving methods of putting ink on paper.

Henry Ford

In this unsteady beginning all the automobile companies struggled. Then, late in the 20th centuries first decade came Henry Ford’s announcement, “I will build a motor car for the great multitude.”

The game was about to change. The age of the automobile was about to dawn and with it the selling power of the printed brochure.

Between 1908 and 1913 Henry Ford revolutionized the automobile with the model T and automobile production with assembly line mass production. Together those two achievements launched both the American consumer and American society into the automotive age.

By 1915 America was home to 100 million people and most everyone wanted an automobile.

Between 1903 and 1917 yearly new car sales skyrocketed over 1000 percent from roughly 18,000 units a year to 1.9 million units a year.

1920 Ford

Through the teens the meteoric rise of the automobile business coincided with the ascent of the advertising agency foreshadowing a coming marriage made in sales and marketing heaven.

New Car brochures would soon reflect the increasing influence of professional copywriters. Copy now emphasized a more detailed, competitive, brand-specific, Feature-Advantage-Benefit message. Riding the tidal wave of automobile acceptance, brochure content, while still wordy, had started a decades-long journey to delivering a more crafted and focused message.

Paper quality received more attention for both its feel and visual appeal. Printing quality improved. However through the teens visual treatments continued to feature forthright mostly staid presentations of the product. The preponderance of images for the most part remained high quality illustration. This was about to change.

The Roaring Twenties arrived fueling a profound transformation of automobile ownership from the exceptional to the commonplace. Automobiles were not only for the wealthy, adventurous or early adaptors, the automobile was for everyone.

Model T price

1908 – $800 1914 – $490 1921 – $310 1924 – $265

By 1925 40% of the work force earned $2000 or more. The average work week had shrunk from six days to five. People had more time, more money and America had 700,000 more miles of paved roads. And just as more people had more money to spend, Henry Ford was lowering the price of new car ownership

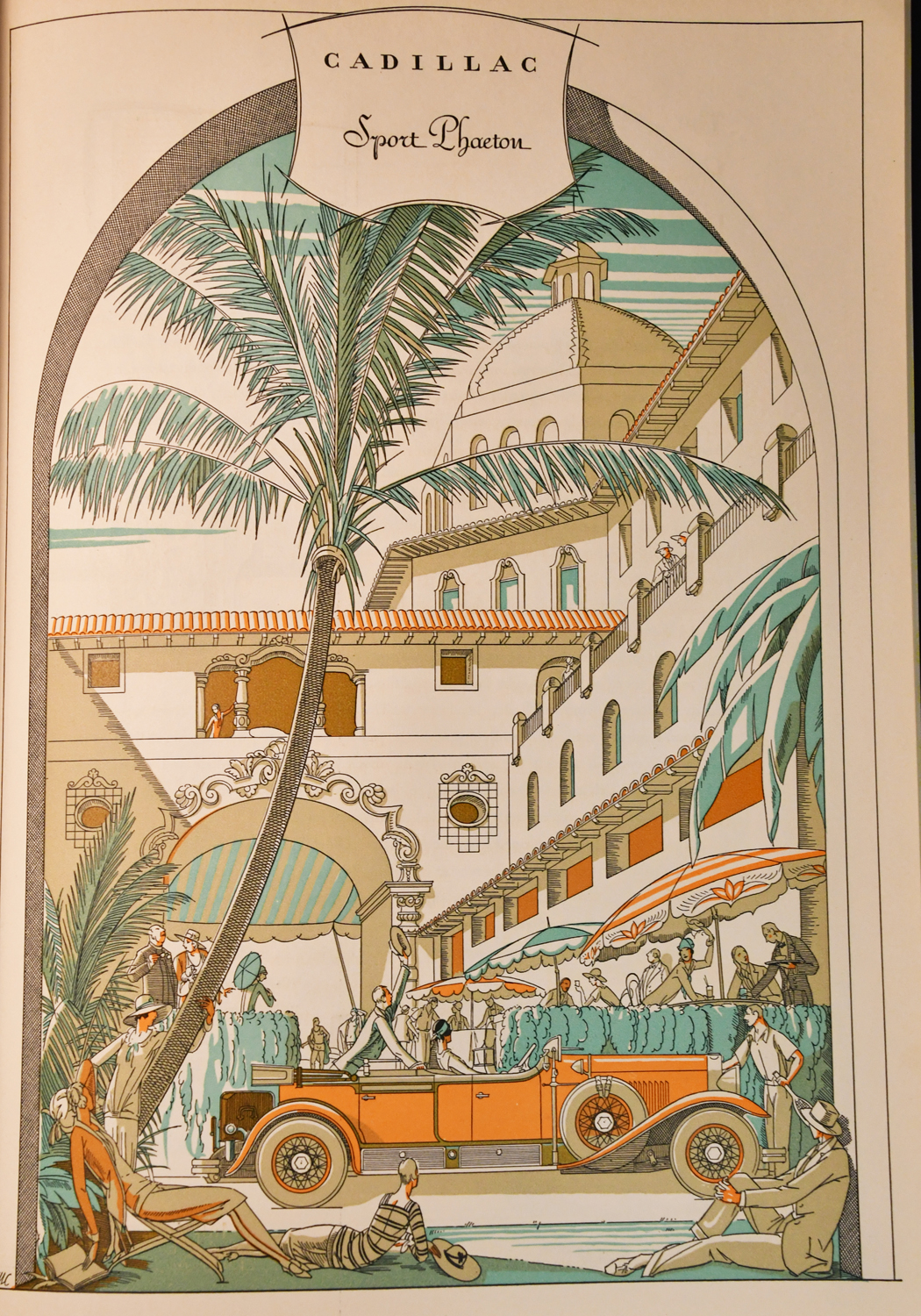

1928 Cadillac

New car brochures entered the decade employing an almost clinically cold display of technical features. That would quickly change. With the suddenly booming economy and exploding appetite for new cars, brochure graphic treatments fanned the flames of desire by displaying automobiles not just as sturdy servants but as sources of excitement, pleasure and fashion. Evocative graphic treatments linked automobiles and lifestyle.

The emergent advertising industry to which manufacturers had delegated much of the responsibility for new car brochure production rose to the challenge and embraced the opportunity with creativity and skill. Visual presentations employed exceptional artistic executions including illustration, etchings, photography and a more compelling use of color.

Automobile ownership soared in the 1920s

YEAR NUMBER OF CARS SOLD

1910 0.45 Mil

1915 2.30 Mil

1920 8.10 Mil

1929 23.10 Mil

America’s love of the automobile had forever changed American life. Depression and war was about to change the world.

“We are the first nation in the history of the world to go to the poorhouse in an automobile”

Will Rogers

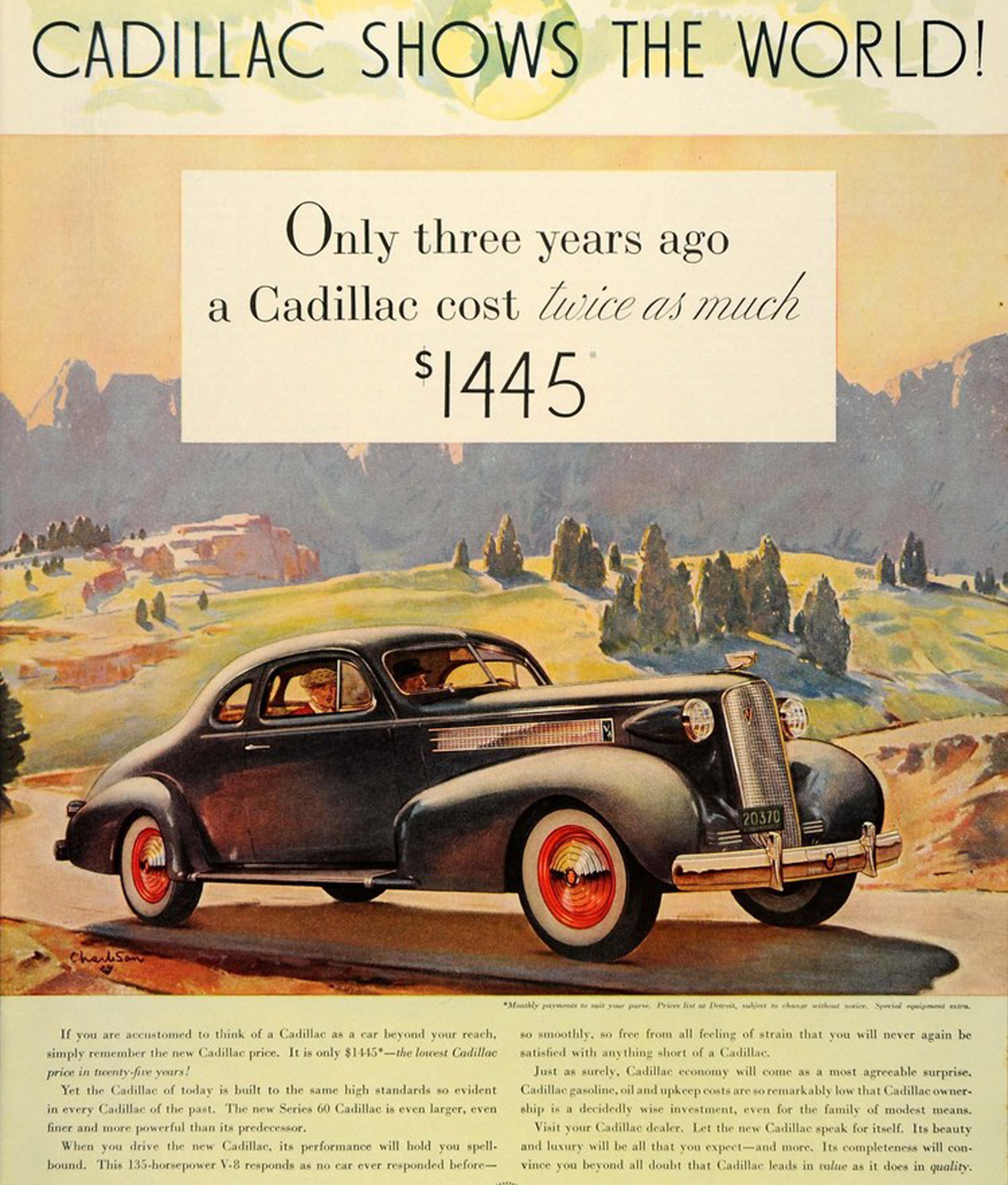

1936 Cadillac

Just at the point when the North American new car brochure was coming into its own, the American economy hit the wall. The depression crushed the automotive industry. By 1932 new car sales plummeted by 75%. Luxury automobile sales literally dried up. Over 30% of the American workforce was unemployed and 40% of nation’s mortgages were in default.

Faced with the challenge of economic conditions, new car brochure copy reflected both an economic reality and, some might say, a Pollyanna-like optimism. Reference to de-contented models, reduced prices, high value, promotion of trade-ins, and financing from GMAC and Ford credit all spoke to the economic truth of the times. However…

1936 Dodge

As the 1930s progressed, new car brochure content, not unlike the glamorous fantasy world portrayed by Hollywood, displayed a comfortable even luxuriant lifestyle that for many was at best a memory.

When present, people depicted in new car brochures were decidedly of the upper middle class or higher. Even lower end brands such as Ford utilized imagery that portrayed the product with a bold countenance.

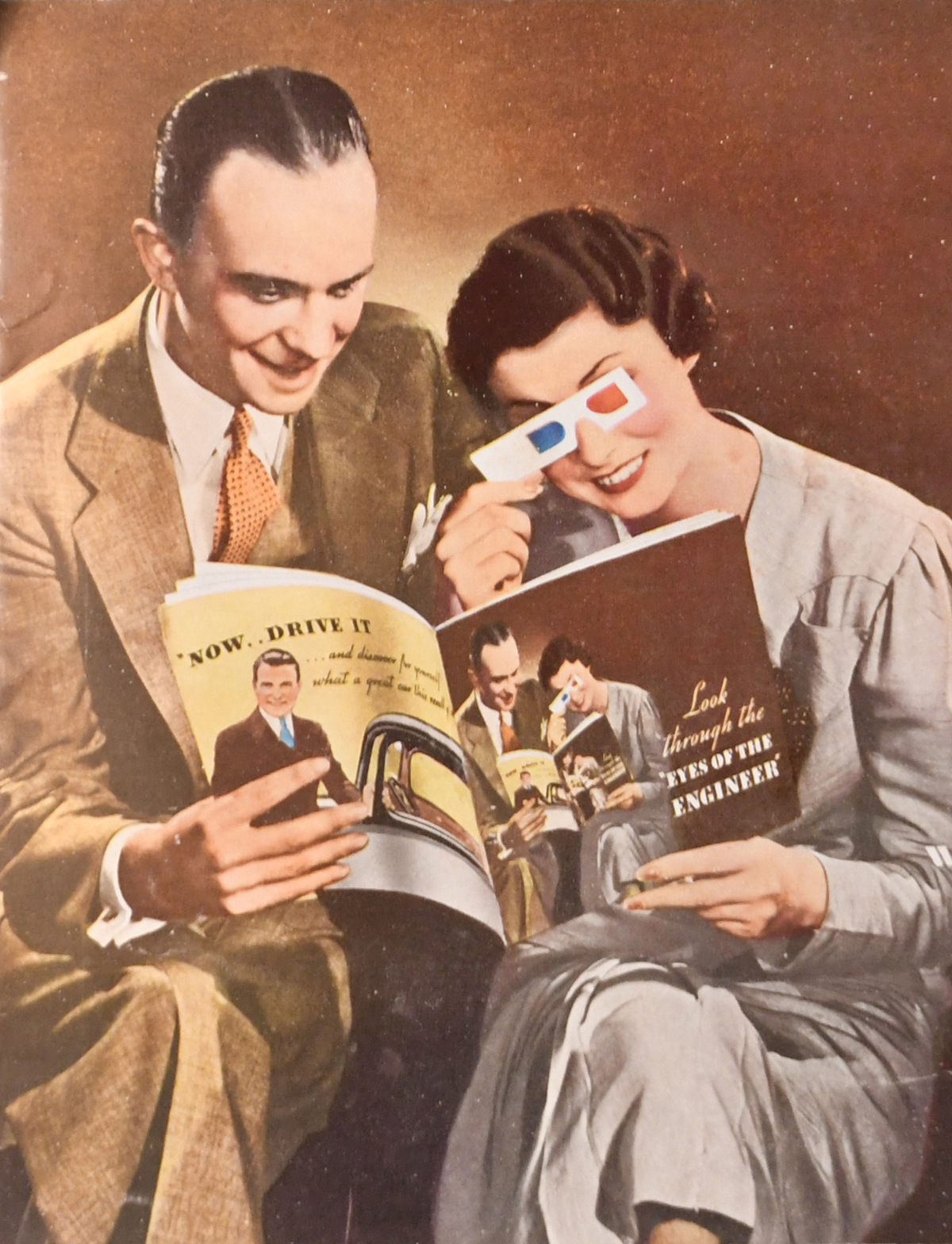

1934 Ford 3D catalog

Luxury makes such as Cadillac employed richly illustrated depictions of life being enjoyed to the fullest. Stronger visual imagery and more graphic layout design gave new car brochures vitality that foreshadowed the evolving visual character that would continue in the post war years.

The creative use of embossing, foil stamping, even 3D imagery together with photography, illustration and true 4-color printing sought to bring glamour to a marketplace and world that was anything but glamorous.

Through the Depression, the automobile industry had battled to fight its way back to solvency with technical innovation. As well, the sales literature that promoted those new products displayed a sophistication reflective of the same level of advancing capabilities. But, now, the automobile industry and the world were about to face an even more virulent challenge – World War II.

Entering Ed Jurist’s Vintage Car Store in Nyack, New York offered a visual wonderment of not only vintage automotive but, as well, vintage aircraft art and artifacts. A 12-cylinder Merlin engine, the type famous for powering the P-51 Mustang, sat proudly cradled where it could be viewed through the building’s large front window that faced the street.

Entering Ed Jurist’s Vintage Car Store in Nyack, New York offered a visual wonderment of not only vintage automotive but, as well, vintage aircraft art and artifacts. A 12-cylinder Merlin engine, the type famous for powering the P-51 Mustang, sat proudly cradled where it could be viewed through the building’s large front window that faced the street.

Powered by two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, the Mosquito had a maximum speed of 415 MPH that made it the fastest aircraft on either side during much of the war. It had a range of 1,500 miles with the ability to carry a bomb load of 4,000 lbs. That bomb load equaled the capability of the four-engine B-17 flying fortress. With a crew of two consisting of a pilot and navigator/bombardier, the Mosquito filled a broad range of roles including bomber, fighter and special operations specialist. One wonderful Special Ops example highlighted the Mosquito’s ability to execute high speed, pin-point, low level attacks. It took place on the morning of January 31, 1943 at a parade in Berlin billed to feature an address by Hermann Goering. As head of the Luftwaffe, Goering had boasted that no enemy aircraft could fly unscathed over Berlin. As Goering prepared to present to the assembled crowd, a squadron of Mosquitoes appeared out of nowhere and effectively put an end to the morning’s festivities. Later that afternoon a second squadron of Mosquitoes put an exclamation point on the RAF’s refutation of Goering’s claim of enemy free skies when a second parade intended to feature a Goering address received the same treatment as the morning festivities.

Powered by two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, the Mosquito had a maximum speed of 415 MPH that made it the fastest aircraft on either side during much of the war. It had a range of 1,500 miles with the ability to carry a bomb load of 4,000 lbs. That bomb load equaled the capability of the four-engine B-17 flying fortress. With a crew of two consisting of a pilot and navigator/bombardier, the Mosquito filled a broad range of roles including bomber, fighter and special operations specialist. One wonderful Special Ops example highlighted the Mosquito’s ability to execute high speed, pin-point, low level attacks. It took place on the morning of January 31, 1943 at a parade in Berlin billed to feature an address by Hermann Goering. As head of the Luftwaffe, Goering had boasted that no enemy aircraft could fly unscathed over Berlin. As Goering prepared to present to the assembled crowd, a squadron of Mosquitoes appeared out of nowhere and effectively put an end to the morning’s festivities. Later that afternoon a second squadron of Mosquitoes put an exclamation point on the RAF’s refutation of Goering’s claim of enemy free skies when a second parade intended to feature a Goering address received the same treatment as the morning festivities.