Cars We Love & Who We Are #38

1938 finds wealthy Romania playboy and auto racing enthusiast Archimedes “Archie” Antonescu poised with a plan as bold as his huge ego to stun the European auto racing community at the 1939 Monte Carlo Rally.

In Search of the 7th Royale (Part 2 –The Build)

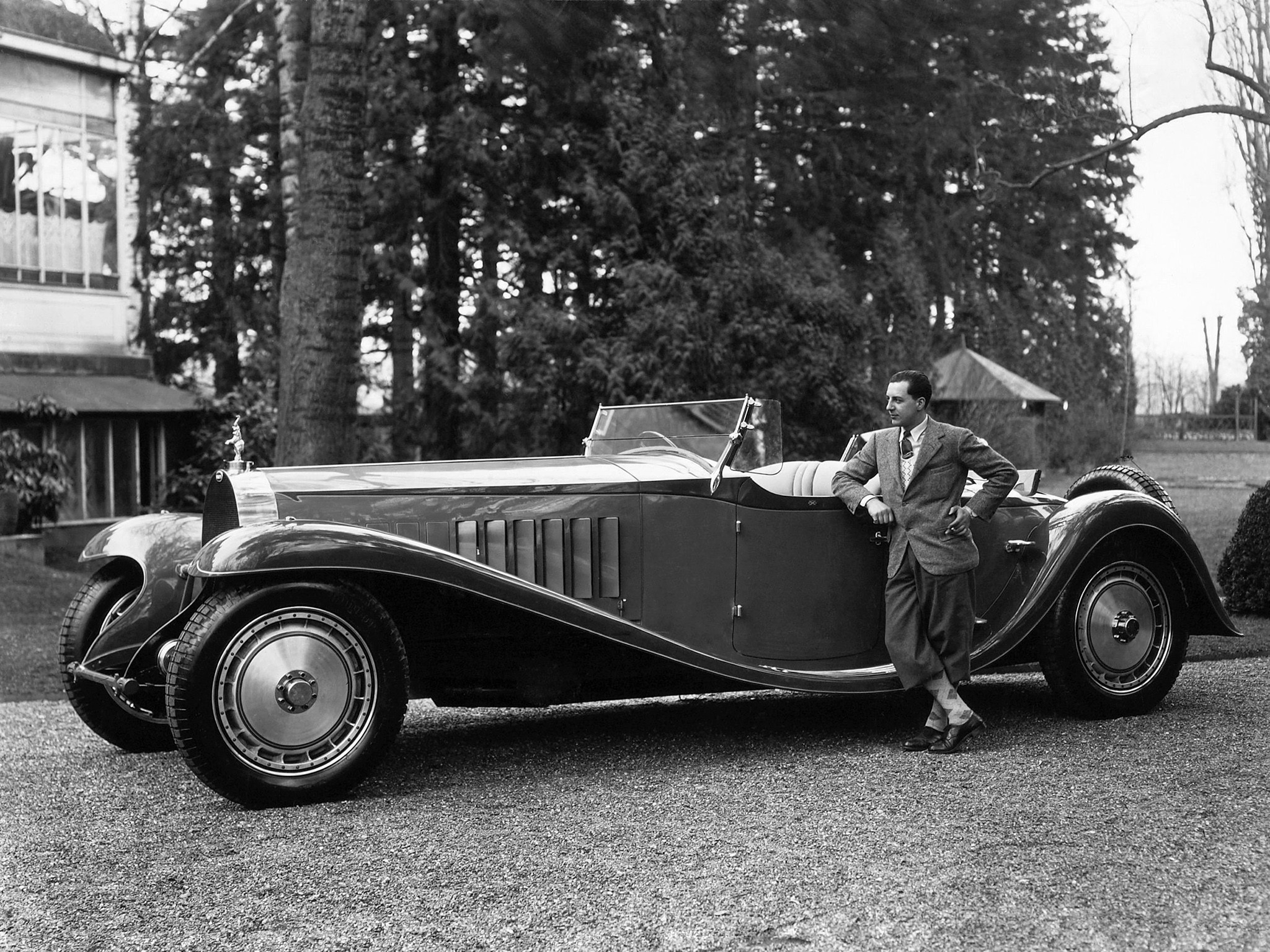

Jean Bugatti with the 2nd Royale

For Europe in 1938 from the standpoint of the gathering storm clouds darkening the skies of global politics, Adolf Hitler clearly towered as “the straw that stirred the drink.” Yet, while “The Fuhrer” by word and deed made clear his bellicose expansionist intentions, a world, still weary and aching from the horror of WWI projected a blind-eye’s willingness to whistle past the coming graveyard.

A world populace tired of war and tragedy seemed intent on pursuing a futile effort to appease and flatter its way out of what many realists viewed as a ghastly inevitability. Despite ruthless Nazi power grabs and brutal savagery inflicted on its own citizens Western media outlets frequently authored fawning articles about Herr Hitler.

November 1938 saw Britain’s Home and Gardens in writing about Herr Hitler and his home state, “It is a mistake to suppose that week-end guests are all, or even mainly, State Officials. Hitler delights in the society of brilliant foreigners, especially painters, singers and musicians. As host he is a droll raconteur.”

In August of 1939, mere days before the start of WWII, the New York Times Magazine in profiling the Nazi leader portrayed Hitler as a country gentleman describing him as, “A man who ate vegetarian, played catch with his dogs and took post-meal strolls outside his mountain estate. The estate featured trappings that the Times reported, “Created an atmosphere of quiet cheerfulness.”

Some famous people outside of Germany sympathized with the Nazi regime. Not the least of which was England’s King Edward VIII who in 1936 abdicated the British crown to marry Wallis Simpson and who then lived a life of liesure touring the realm of high society.

For affluent friends of the Third Reich, the later 1930s offered heady times indeed. Archie with his seemingly boundless wealth from the vast Ploesti oil fields of Romania enjoyed, as well, the benefits of his symbiotic ties with the Nazi powers that be. For Archie, living at the crossroads of great wealth and political connection inoculated him from any discomfort much less the devastation inflicted by the Great Depression that plagued the world around him.

Ettore Bugatti

For Ettore Bugatti, “Le Patron,” his creations captured thirty-eight Grand Prix victories and over 3,000 wins in races of lesser stature. Among the ranks of the 20th century’s first generation of great visionaries, Bugatti sat on the highest throne in the pantheon of automotive gods. As inspired designer, intuitive mechanical genius and master of form and function he stood alone. His gift for translating his genius into fine automotive art made his eponymous brand synonymous with speed, beauty and exclusivity.

Bugatti’s life and business centered in Molsheim, France where his grounds exuded a presence far beyond that of “business.” Adjoining his factory stood a magnificent chateau. A glorious residence, yes, but even more, an estate over which Bugatti resided much as a lord of the manor. Here in the 1920s and early 1930s as Bugatti’s geographic center of power, Molsheim served as the stage upon which “Le Patron” entertained royalty, elite customers, and world class drivers as well as friends and family.

Being wined and dined as a valued customer at the Bugatti chateau by “Le Patron” himself frequently featured in Archie Antonescu’s dreams.

Following labor unrest in 1936 at Molsheim that had soured Bugatti on his business, he handed over the day-to-day operation to his son Jean Bugatti and basically retired to Paris.

Archie’s call in early 1938 reached a bored and restless Bugatti as “Le Patron” gazed out the window of his Paris apartment located on the fashionable Rue Boissiere. As with the many days before, this gray winter day offered “Le Patron” little promise. Archie’s timing could not have been better. Awash in memories of the good times gone and bitter at how the Great Depression had choked the vitality from the company that embodied his life, Bugatti responded with interest to the wild dreams of the wealthy Romanian playboy. The caller’s frequent use of the phrase “money is no object” heightened Bugatti’s interest. If what he heard would prove to be true, which it would, it presented Bugatti with the opportunity to resurrect one of his grandest dreams in an even grander manner. Simultaneously, the creative fire in his soul had been ignited at the thought of glory reclaimed. The call populated with a wealthy prospect’s dreams and a master’s vision concluded with an agreement for the two to meet. The call ended leaving minds racing, hearts pumping and plans taking shape.

La Fenier, a quiet and rustic restaurant nestled in the wooded countryside outside of Paris, with its simple menu, capable kitchen and adequate wine list had been Archie’s choice for the meeting place. Above all it suited Archie’s desire for secrecy.

The understated black Citroen Traction Avante parked outside had been Archie’s choice for anonymity’s sake rather than arriving in the outrageously and sublimely beautiful silver V-12 Delahaye 145 Franay Cabriolet in which he preferred to be seen, and noticed. Like a hive bursting with too many bees, Archie vibrated with anticipation at meeting the great Bugatti while feigning nonchalance. His gaze locked on the gravel parking lot.

1936 Bugatti Type 57 Stelvio

With the sound of stones crunching beneath tires, Archie’s gut clenched as a strikingly handsome black Bugatti Type 57 Stelvio 4-seat cabriolet pulled in to literally grace the parking area. The beautiful Stelvio defied Archie’s expressed wish to attract no attention. Then Archie realized that the pride expressed by Bugatti’s choice of vehicle displayed exactly the willful genius Archie wanted to enlist in creating the car of his dreams.

After exchanging initial pleasantries, and with a shared fluency in Italian, Archie and Bugatti dove into the purpose of their meeting. To eliminate any concern on the part of Bugatti, Archie addressed a common stumbling point when discussing compensating a master for the production of an original bespoke creation. To produce Archie’s Royale, money would be no object. In a time when the average worker’s annual salary, if he had a job, stood at roughly $1,400, and the average cost of a new car was $640 a Bugatti Royale would coast approximately $45,000. The un-bodied chassis and drive train cost $30,000 with another $15,000 for the custom body. Archie guaranteed Bugatti an initial working budget of $100,000, more if necessary, to get exactly the car he wanted. The promise of this dream project infused Bugatti with a vigor absent for years. Eager, engaged and alert the Bugatti of old focused his full attention on absorbing the details of the dream that would be his responsibility to make a reality. It quickly became evident to “Le Patron” that the process would involve a significant level of vexation. This client made it clear that in developing a unique design he would demand incorporating some new and, in some cases, very un-Bugatti like executions.

The iron willed Bugatti bristled in recognizing that this opportunity came at the price of sharing critical decision making responsibilities with “the Romanian.” Bugatti possessed a well-documented reputation for a stubborn resistance to change. His recalcitrance even extended to opposing the updating of flawed Bugatti design elements with new ideas that would benefit his vehicles. However, in a profound expression of self-awareness tinged with the flavor of personal gain, Bugatti recognized the need to accept a co-authoring of sorts. He could not turn his back on creating the ultimate Royale and reinvigorating the Ettore Bugatti of old. Inside, he also knew that while there might be two bosses there would still only be one “Le Patron.”

Archie unaware of Bugatti’s internal turmoil, felt totally secure in outlining his ideas. In the decade since the Royale appeared, many advancements at Bugatti and across the automotive industry had significantly elevated the sophistication and capabilities of performance cars. Archie wanted it all.

Archie declared that extensive use of aluminum in the body, chassis and engine block would be a must as a means to pare the Royale’s elephantine weight. Not a new idea, Europe throughout the 1920s and 1930s made extensive and artistic use of aluminum in limited production and race cars with cost being the limiting factor. Bugatti himself had used aluminum in some of his earliest cars. With Archie’s wealth and commitment, cost would not be a problem.

Festivities at the Monte Carlo Rally

For the chassis frame, rather than steel, Alpax a light alloy material with which Bugatti had experimented would be used. Light alloy wheels and brake drums motivated by Bendix hydraulic brakes would upgrade Bugatti’s traditional cable brakes.

Significant improvements to the massive Royale power plant intended to provide for greater efficiency and performance would be based on advancements introduced in Bugatti’s magnificent Type 57 in 1936. Archie’s Royale would be supercharged with twin overhead camshafts and dry sump lubrication. Transferring this massive power to motion would be a 4-speed manual transmission. Based on Bugatti’s experience with the Type 53, Archie’s Royale would have 4-wheel drive and an independent front suspension to better face the possible deep snow and the certainty of rough roads. It would even have a two-way radio that had just been introduced by Motorola in America. Intended for police use, it would facilitate communication with his support team.

Archie envisioned his Royale bursting on the scene to rave reviews from a stunned motoring press. It would capture the imagination of the racing world gathered for the 1939 Monte Carlo Rally. It would be hailed as the seamless integration of all that represented the best of Bugatti.

Bentley Blue Train

But what of his Royale’s body? The skin had to be equal to the magnificent entrails. In Archie’s mind it had to capture the masculine power of the famed Bentley Blue Train with an elegance worthy of display at the Louvre. Only one person merited Archie’s trust. The visual presence of the 7th Royale had to come from the mind of Jean Bugatti, Ettore’s son and the inspired design genius behind the exquisite Bugatti Type 57 SC Atlantic.

Bugatti Type 57 SC Atlantic

Here the two bosses had a difference of opinion and Bugatti exercised his personal perspective as the preeminent “Le Patron.” Archie stated his desire to employ body builder J. Gurney Nutting of London, England because of its history with the Bentley Blue Train. Bugatti had other ideas. For two very good reasons he adamantly advocated for Carrossier Gangloff of Colmar, France. First, by the mid-1930s Gangloff had established itself as Bugatti’s most important outside coachbuilder with enormous success in uniquely expressing Jean Bugatti’s iconic Type 57 concept with over 180 individual Type 57 bodies created. Bugatti knew this would be the Carrossier to bring his son Jean’s design for the Romanian to glorious life. Secondly, the close proximity of Molsheim and Colmar in Alsace offered a great advantage. Bugatti understood that the extent of his Romanian customer’s wish list made time a precious commodity. The difference between shipping a chassis and a body between Molsheim and London versus driving the short distance between Alsatian neighbors Bugatti and Gangloff could well determine the difference between making and missing critical deadlines. Like a force of nature on this decision Bugatti could not be denied. Gangloff would body the 7th Royale.

Their conversation which began with the sun high in the sky concluded as the colors of the coming sunset painted the Parisian sky with an orangey rose hue. With hands outstretch, Archie with a vigor that seemed to gush from his every pore and “Le Patron” with a firm confidence that seemed anchored in the earth upon which he stood, shook hands to seal the deal.

Returning home though the wooded countryside, the warm dappled light of the fading sun danced across the hood. Archie, with a few hill climbs and local road races under his belt fancying himself a skillful driver, attempted to flog the somewhat anemic Citroen down the twisting country road. Sporting a smug smile of delighted self-importance Archie basked in the experience of dealing directly with the great Bugatti in person. He reveled in the success of the meeting. The exhilaration of seeing his dream come to life fired his imagination. His thoughts now turned to the 1939 rally itself.

The Monte Carlo Rally rules significantly rewarded drivers setting out from the most distant starting points. His choices had narrowed to three cities Athens, Greece; Stavanger, Norway; and Tallinn, Estonia. Six of the last seven winners had started from one of those three sites.

Tallinn had significant oil shale deposits of considerable interest to the Nazi war machine and the Antonescu family. Archie could rely on having significant resources available to him in Estonia. It made his decision easy. His Royale would start the Monte Carlo Rally in Tallinn.