Cars We Love & Who We Are #31

Like many car enthusiasts, Leslie’s father, Pete LaFronz, had spent a good part of his adult life pleasantly consumed by an ongoing love affair with the car of his dreams. For over forty-years Pete, with his money and time, passionately stoked the flames of his obsession for a single family of sixteen-cylinder Cadillacs, the late 1930s “Sixteen.” For model years 1938 through 1940, the second and last generation of Cadillac V-16s or the “Sixteen,” as they were know, stood as the pinnacle of the American automotive hierarchy. Pete had spent hundreds of thousands of dollars amassing the bodies and parts to build two maybe three Olympian specimens. Largely a mass of bodies, parts and pieces, no one, except Pete, really knew what he had. Then Pete died leaving daughter Leslie as the Executor of his estate.

Meet Pete’s daughter and non-car enthusiast, Leslie LaFronz.

When the collection outlives the collector, a daughter’s point of view

A few weeks back a friend of mine had asked if I could help her niece, Leslie LaFronz, get a handle on what the niece’s recently deceased car enthusiast father, Pete LaFronz had left behind in a garage with no instructions.

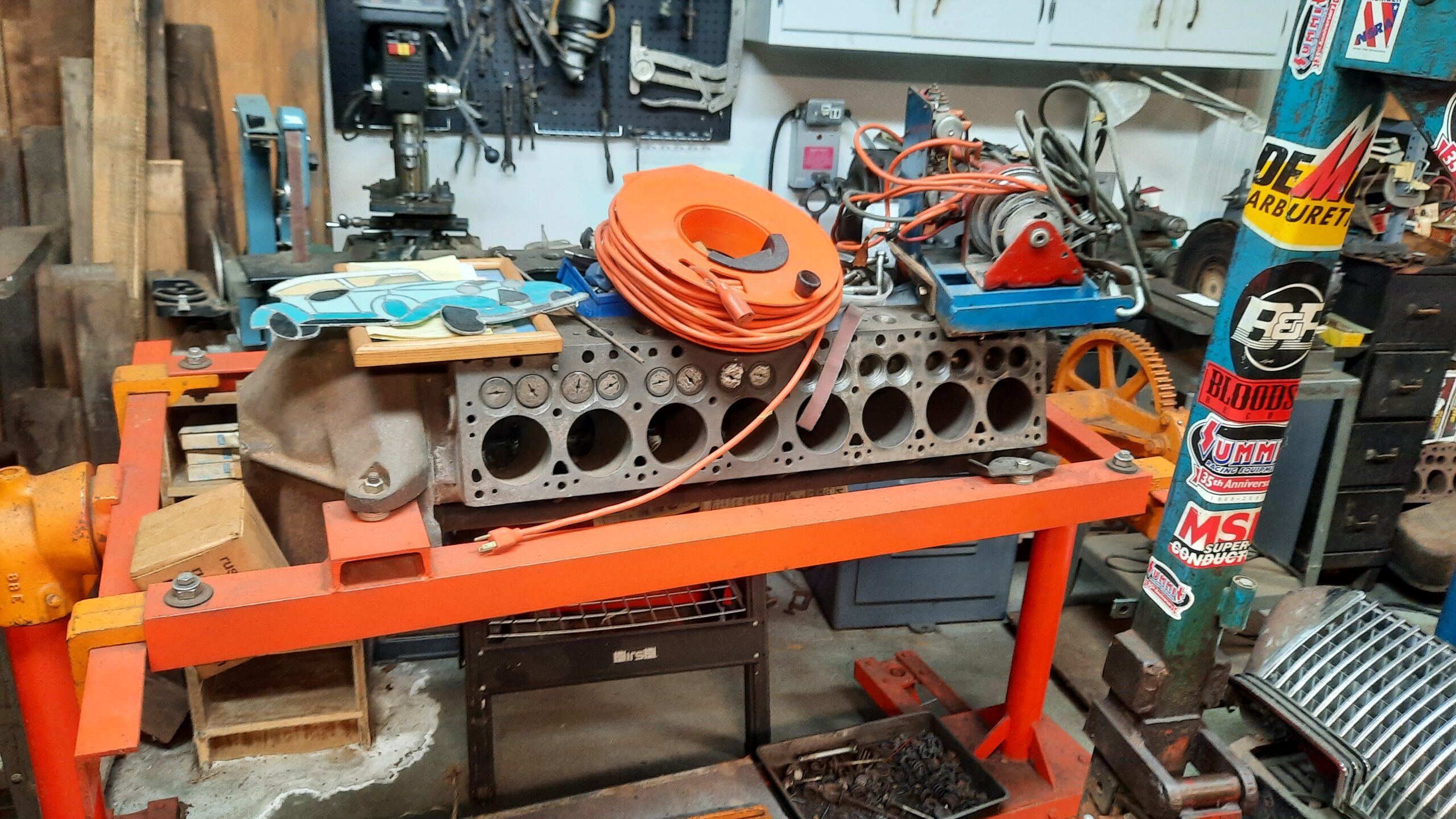

Crunching through autumn leaves on the upwardly sloping gravel driveway, I passed a neat suburban single family home of 1930s vintage. Moving on I approached a handsome-two story carriage house capable of holding six cars. A single hint of its contents greeted me in stony silence. Locked in a rotisserie stand, a chassis that to the naked eyed looked worthy of a Peterbilt truck stood sentry. Though long exposed to the elements, it looked defiantly solid.

The carriage house I would soon learn was built two decades ago by Pete, who I would also learn possessed excellent technical and fabrication skills. Blessed, as well, with boundless energy and a strong will, Pete held no

fear of daunting projects. I would soon see further evidence of that fearlessness manifested on the other side of the secured garage doors.

Outside the garage a middle aged woman with an air of the overwhelmed busied herself with boxes of clutter amidst a scatter field of random debris. Such possessions, orphaned by the loss of their departed owner, express a cold absence of meaning as they no longer  possess a context drawn from the life force of the individual to whom they once belonged.

possess a context drawn from the life force of the individual to whom they once belonged.

Looking up from her task she introduced herself as Leslie LaFronz. A successful field hockey coach at Kean University, Leslie projected the quiet resolve of a capable woodsman who has found herself in a strange forest facing a challenge without a ready solution. One of Pete’s four daughters and Executor of Pete’s estate, Leslie has just begun scratching the surface of a daunting task that awaited her. With a tone blending foreboding and humor Leslie, facing back at me from the garage, asked, “Ready for this?” I was not.

Staring straight ahead as the garage doors opened to reveal its contents, I quickly grasped how truly fearless and I am sorry to say unreasonably optimistic, dare I say self deluded, Pete had been.

Feeling for all the world like the little kid in the movie “Close Encounters” who opens the back door to be overwhelmed by the unknown, I had not been prepared to face a significant percent of the remaining and rarest of the second generation Cadillac Sixteen. Filling the first floor of Pete’s garage can best be expressed as a Gordian knot of rare Cadillac bodies, parts and pieces, many of them priceless others worthless. To differentiate one from the other screamed for the truly educated eye of a vintage Cadillac expert. Apart from a comprehensive array of machinery to carry out a restoration, the six-bay garage floor served as home to a four-door convertible Phaeton, a 2-door convertible and a Coupe. Leslie recalled her father claiming that all the parts where there to do total restorations of at least two cars. Amazingly the bodies appeared original, solid and suffering from minor surface rust if any at all.

Looking about the garage “Sixteen” engines, short blocks, solid body panels and bright work resided within a perimeter defined by ceiling high shelves filled with neatly organized bins of parts, some labeled, some not. Like grout on a tile floor, any free space between this treasure trove of vintage parts was packed with cartons of magazines, books and random car related paraphernalia. Just trying to navigate through this maze of treasure and trash posed a physically challenging task. I was speechless. Leslie was not.

“There is much more upstairs, you know. Would you like to see that too,” Leslie asked posing the question with a blend of challenge to a newcomer and resignation to more evidence of a crushing burden she must shoulder. Climbing the garage stairs, the mantra of the late night infomercial “But wait, There’s more!” came to mind. And, yes there was more, many more parts and pieces.

Having surveyed the scene as best I could, I stood outside the open garage to share some thoughts and commiserate with Leslie in acknowledging the challenge she faced. It was then that Leslie added in an off-hand manner, “Then, of course, there is everything upstate.” Indeed, there is more. “Oh yes,” Leslie said, “My dad had stored a number of Cadillacs out in an open field in Sullivan County New York. He bought the property because he needed more space. I had to go see.

Driving through the back roads of rural Sullivan County brought me to property along a narrow country lane with an abandoned house and a large field with a fenced in area. Inside resided five late 1930s Cadillacs that, while solid, had begun the biblical journey of dust to dust.

For a knowledgeable car guy or gal, the task Pete, a loving father, had bequeathed to his loving children would have been a wicked time and energy consuming challenge. For four daughters with no collectible automobile experience or interest it loomed as a mind numbing abyss filled with unanswerable questions. Did it need to be this way?

Other than his family, Pete loved nothing more than immersing himself in the history and substance of the 2nd generation Cadillac “Sixteen.” With only a total of 508 built over its three model year production run from 1938 to 1940, the Sixteen was doomed to extinction courtesy of political, economic and technical realities for which no defense existed.

Cadillac introduced the V-16 just as the Great Depression crushed the market for Olympian cars. Timing could not have been worse. Of Cadillac’s total V-16 production of 4,376 units, two-thirds of all sales came in its first model year of 1930. Then the Depression dug in and ground on. Despite its stature as the pinnacle of automobile luxury and performance, Cadillac V-16 sales steadily declined through the Depression until 1937 when conventional wisdom believed Cadillac would discontinue the V-16. But, no, for model year 1938 Cadillac doubled down and introduced a 2nd Generation V-16. This Sixteen would, fifty years later, capture the heart of Pete.

Cadillac’s second generation V-16 introduced a totally new 431 cu. in. V-16 engine that was lighter and more efficient while delivering performance superior to the previous year’s model. Its exterior treatment and interior appointments supported Cadillac’s claim that the new Sixteen stood as the “World’s Most Luxurious Motor Car.” Over its three-year run the Sixteen came in six models; 4-door Sedan, 2-door Coupe, 2-door Convertible, 4-door Convertible, 4-door Town Sedan and 4-door Town Car. Pete had collected four, lacking only the Town Sedan and Town Car.

The demise of the Sixteen came at the hands of its value proposition. Despite its 16-cylinders, new technologies made the modern V-8 equally attractive while sharing the same body styles. And then there was the matter of price. The Sixteen cost over $2,000 more than the V-8. It has been pointed out that for the same price as a Sixteen, one could buy a V-8 powered Cadillac 75 with the same body and features plus a new Buick convertible and a new Chevrolet with change left over. The last Sixteen left the factory in December of 1939. None of this mattered to Pete.

In supporting his passion there appeared no limit to the lengths to which Pete would go to add to his store of authentic Sixteen parts and pieces. His efforts seemingly knew no bounds. No bounds indeed. Surveying Pete’s garage and upstate property revealed the extraordinary fruits of his efforts.

Leslie says, “Once in a while we would talk about his cars and he would reveal that he had over $250,000 in parts and pieces.” Pete would show Leslie an emblem for which he had paid $2000. She would look but could not see the value.

It would not be unusual for Pete to go to a show carrying a paper bag containing $10,000 in cash just in case he saw something he wanted. Leslie says, “He always dealt in cash. He also always wore his worst clothes in an effort to get a good deal. Never used a credit card.” Yet, despite his obsession with the Sixteen, Pete, over 40-years, never restored one.

Why did he go through all the trouble? When asked Leslie says, “Maybe it was about the hunt to find the pieces. Maybe the hunt gave greater pleasure than actually driving a completed car.” Leslie continues, saying, “We could never figure it out. We didn’t need to. If he was happy. We were happy.” The family feeling pretty much held that it was his money. He worked for it. He should enjoy it. Who are we to ask?”

Then, Pete died and with him went the passion and the knowledge leaving Leslie and her sisters with his collection and little if any understanding of what they now owned. When posed with the question – What could Pete have done to better prepare for the inevitable? – Leslie had some interesting thoughts.

Pete’s story offers valuable lessons for other car enthusiasts who do not care to look down the road when it comes to estate planning for all they have accumulated under the banner of their collectible automobile passion.

Leslie’s experience offers some valuable suggestions for those who want to do the right thing for the people they love who will be taking possession of the cars they love.

Leslie, a bright, no-nonsense and loving daughter makes it clear that much could have been done if her father had chosen to cooperate. Leslie had repeatedly suggested to Pete that they take a video camera and walk around the garage and capture his thoughts on the meaning, purpose and value of various items. Leslie says, “We could have recorded him pointing to things and explaining what they were and what he paid for them.” Equally if not more important in Leslie’s mind would have been for her dad to identify his assessment of the present market value of his collection. Another excellent idea of Leslie’s was her desire to have her dad make a list of friends and associates. Those possessing valuable knowledge could be an exceptional resource for Leslie as would a list of those with an interest in purchasing part or all of the collection.

In retrospect the daughters knew the problems they would face when Pete passed. Though Pete possessed great hearing, he turned a deaf ear when they suggested that he tag things as to year and purpose. Leslie says, “My sister even bought the tags, everything to do it.” She continues, “My dad said he would do it but it was so close to the end that he never did.”

In speaking to the Drivin’ News reader whether the collection belongs to you or an aging parent Leslie says, “Specific preparations need to be made for the sake of the collection and for those to whom it will be left.”

Leslie says, “I think you want your life in order. If you’re passionate about your family, or your legacy, then do the right thing. Have your will drawn up and include the description, evaluation and plans for disposition of your collection. If you want somebody to have something, make sure that they know that you have it in writing somewhere. It’s just so much easier for those who must sort it out later.”

In Leslie’s mind, making plans for the inevitable represents a necessary part of the proper stewardship of a collection, regardless of its size whether one classic car or one hundred.

In reflecting on one’s responsibility to a collection consider estate planning in the sense of providing fuel stabilizer for winter storage. It ensures your car will be ready to drive come spring. Except in the case of estate planning you are ensuring that your collection has the best chance of being loved when you will longer be at the wheel.

Drivin” News will be revisiting Leslie in the future to see how this challenge resolved but for now these are Leslie’s take away points to consider:

-

Record a video walking tour of a collection with commentary by the owner

-

Tag components identifying:

-

What it is.

-

What it cost when purchased

-

Its present value

-

-

Create a list identifying

-

Friends with knowledge about the collection

-

Individuals with an interest in buying part or all of the collection

-

-

Include the written document outlining your plans for the disposition of the collection contents.

-

Meet with an attorney