Conversations With People We Value #23

All Americans had been warned. No meaningful correspondence should be tossed into a hotel waste basket. Assume that your room has a listening device. Any private conversation should be held outdoors in the open square. These warnings were to be taken seriously when working behind the Iron Curtain during the cold war. So recalls Patty Moore a member of a unique team of exceptional design talent assembled by 20th Century industrial design icon Raymond Loewy. Talented and brash, the team faced the daunting challenge of creating a world car for the Soviet Union to market around the globe in the 1970s.

Though an American citizen, Mr. Loewy was French by birth and thus acceptable to the Soviets. However, the small team he assembled to create the design was 100% American.

For American and Soviet alike, pronounced egos and sharp elbows bruised at every turn. Conflicting creative styles and attitudes born of clashing ideologies destined the project to be equal parts car story and John le Carre novel.

In the early 1980s, I had been in contact with Mr. Loewy as well as members of his design team. I have taped interviews conducted in 1982 with design team members as well as what may be the only existing images of the concept car.

What follows is the birth story of the ill-fated Moskvitch XRL.

Raymond Loewy’s 1970s Soviet world car adventure

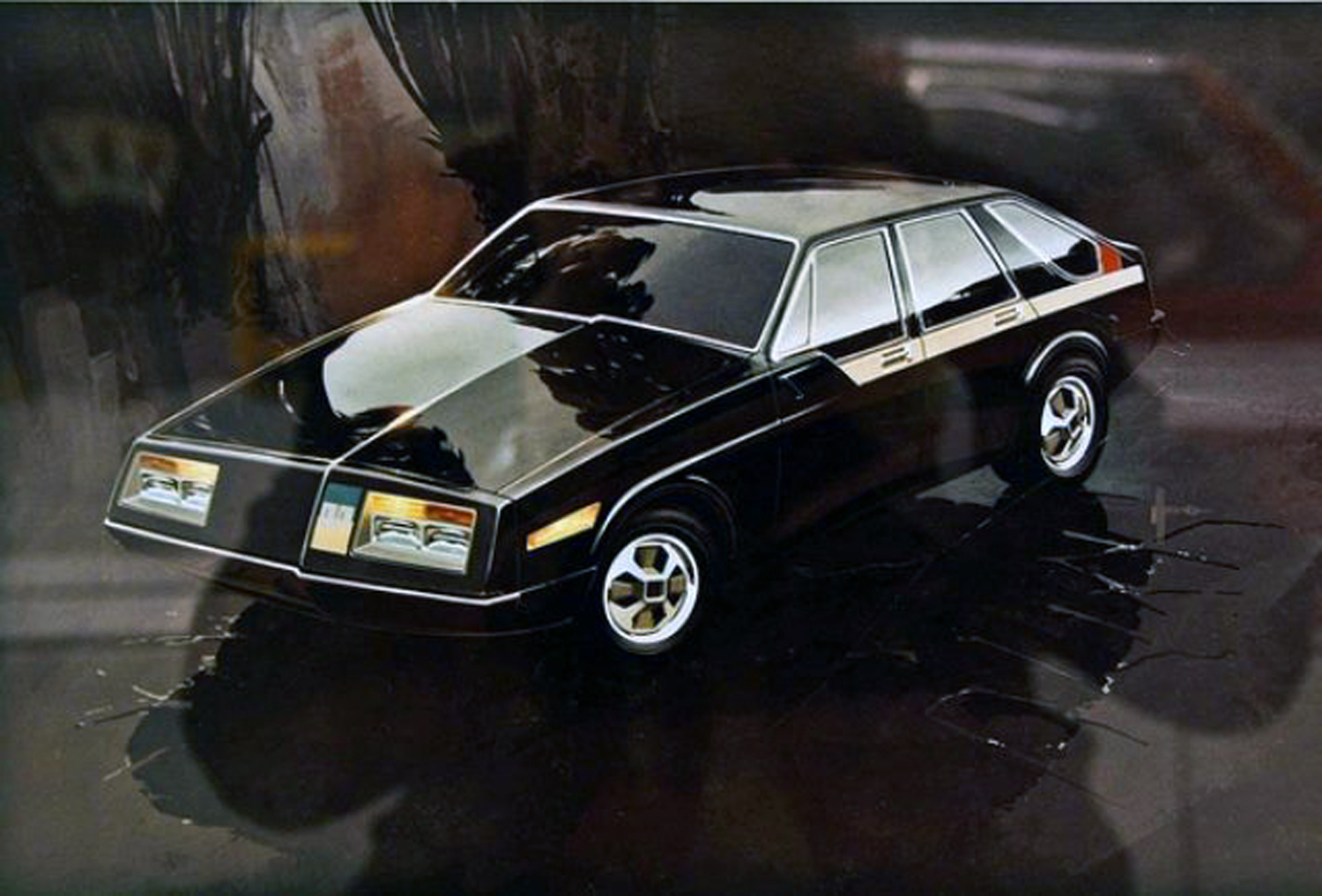

Initial version of Moskvitch XRL

For the Soviet Union in the 1970s, it was a bold undertaking. The Soviet plan called for producing a family sedan, the Moskvitch, to sell in the new car showrooms of the western economies. To pull it off they reached out beyond the Iron Curtain to a Frenchman by birth and a naturalized American citizen by choice. He would be the man bold enough to succeed. He was Raymond Loewy, father of industrial design, creator of the Avanti, Studebaker starlight coupe, Shell logo, modern Coca-Cola bottle and hundreds more cultural icons.

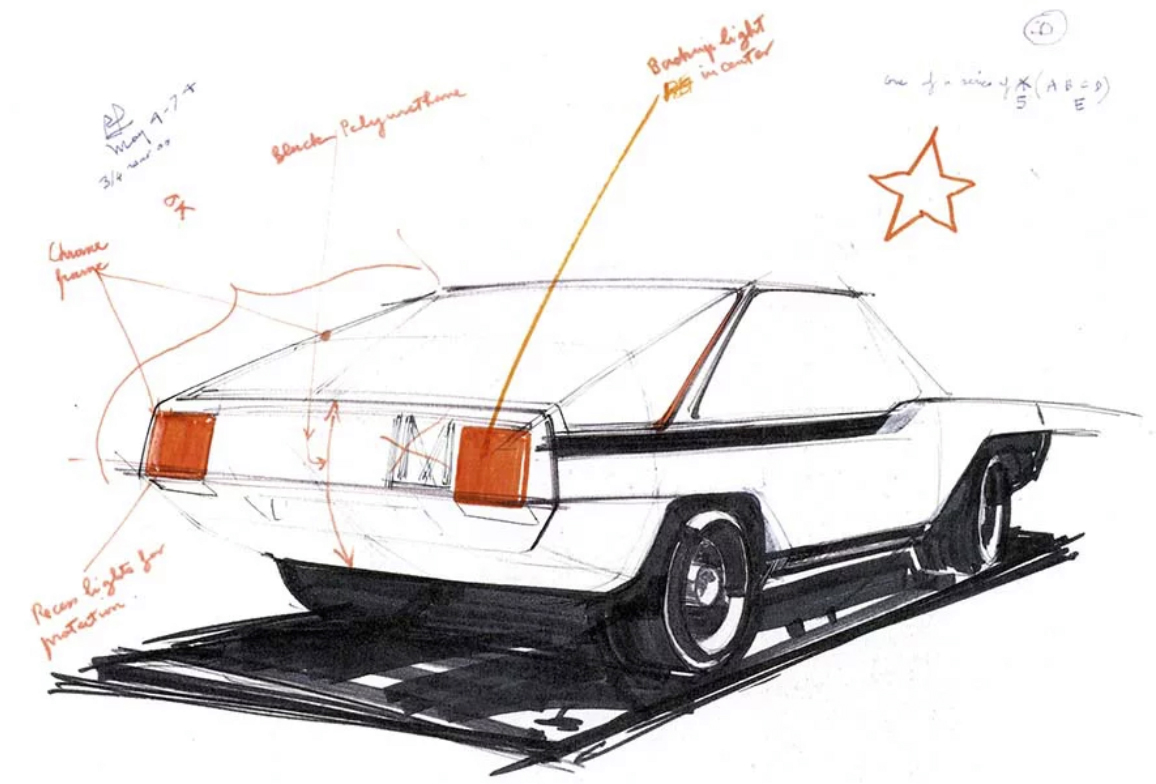

Early Moskvitch sketch

In this era of Nixon and Brezhnev, Détente was in bloom. This warming of relations coincided with a Soviet 5-year plan that emphasized aggressively marketing consumer goods to the West. The red stars had aligned to create a profound need for a serious upgrade of Soviet consumer product aesthetics.

Loewy anticipated the extraordinary opportunity. As the creative genius who fathered the field of industrial design, he enjoyed a good relationship with the Soviets that dated back to the early 60s. The Russians liked and respected Loewy. Loewy had cleverly positioned himself to achieve something no one had done before or would do again.

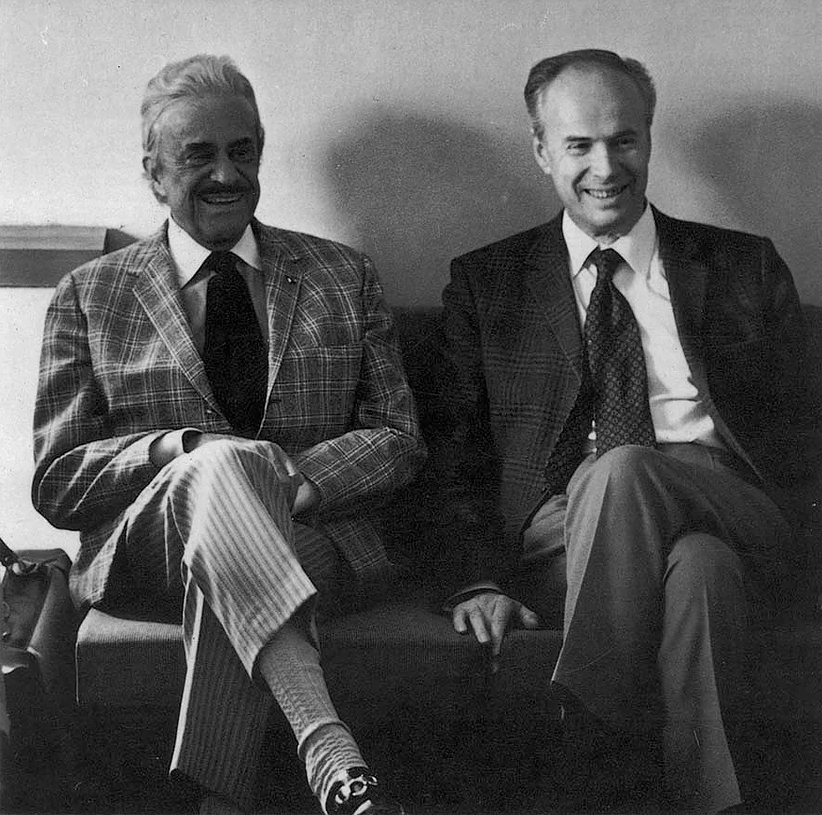

Signing of 5-year agreement with Dr. Jermen Gvishiani of VNIITE

In signing an historic design services contract with the Soviet Union, Loewy stands as the first and only person to direct a design exchange between an American company and the Soviet Union. In his own words Loewy called this design exchange, “the most important achievement of my long career.” In addition to the Moskvitch, the contract called for the design of a broad spectrum of products including clocks, cameras, motorcycles, hydrofoils and more.

1974 witnessed Loewy assemble a unique collection of gifted American designers in their 20s and early 30s to create the Soviet dream car, the Moskvitch XRL (X – experimental, R – Raymond, L – Loewy).

Team members included Patricia Moore, then in her early twenties, and responsible for the interior. Moore would go on to be named the Most Notable American Industrial Designers in the history of the field. And in 2000, was honored as one of The 100 Most Important Women in America.

Raymond Loewy and Yuri Soloviev

Syd Mead served the team by creating contextual visualizations of the Moskvitch design. Mead would later become famous as a neo-futurist concept artist who visualized environments for science fiction films such as Alien, Tron and Blade Runner.

Though well respected by the Soviets, Loewy held no great admiration for their political system. Loewy’s impressions from his Soviet experiences where sharp and divided. He had great respect and admiration for many of the individuals and professionals with whom he dealt. Yuri Soloviev the Director of VNIITE (The Soviet All-Union Scientific Research Institute of Industrial Design) was one. However Loewy felt nothing but loathing and contempt for the communist system of governance. In a letter to partner William Snaith following Loewy’s first visit to the USSR in 1961, Loewy wrote, “In spite of the wonderful welcome, we returned more than ever convinced that communism is the greatest hoax in the history of the world. I cannot tell you the dreariness, the gloom of life under this system.”

Loewy after signing of 5-year agreement standing with iconic Avanti designed by Loewy

When worlds collide might best describe the cross cultural interactions between the two decidedly different cultures.

It evidenced itself dramatically when a young Patty Moore took a team of six visiting Soviet Project Managers and a Soviet psychologist on a walking tour of Manhattan. The Psychologist viewing the experience from a psycho-social basis was interested, intrigued excited by everything.

The Soviet engineers and scientists, however, displayed the attitude that the Soviet Union unquestionably stood superior to America. They clearly viewed America as the enemy and a competitor.

As the late afternoon sun lengthened shadows, the Russian Managers crossed Manhattan’s 5th Avenue. Like Darwin first touring the Galapagos, they faced a world both foreign and fascinating. They swam through waves of American culture swirling in the canyons of New York City. High heels, long legs, bell bottoms and bright colors. Late summer of 1975 greeted them. They had come to see the automobile that Raymond Loewy, iconic father of industrial design has created. They ended up getting much more than they ever could have dreamed.

During the walking tour the Soviet psychologist would frequently become excited and animated at the New York experience. His exuberance would be quickly and consistently squelched by senior officials sharing the tour. In Russian he would be directed to refrain from speaking in such positive terms.

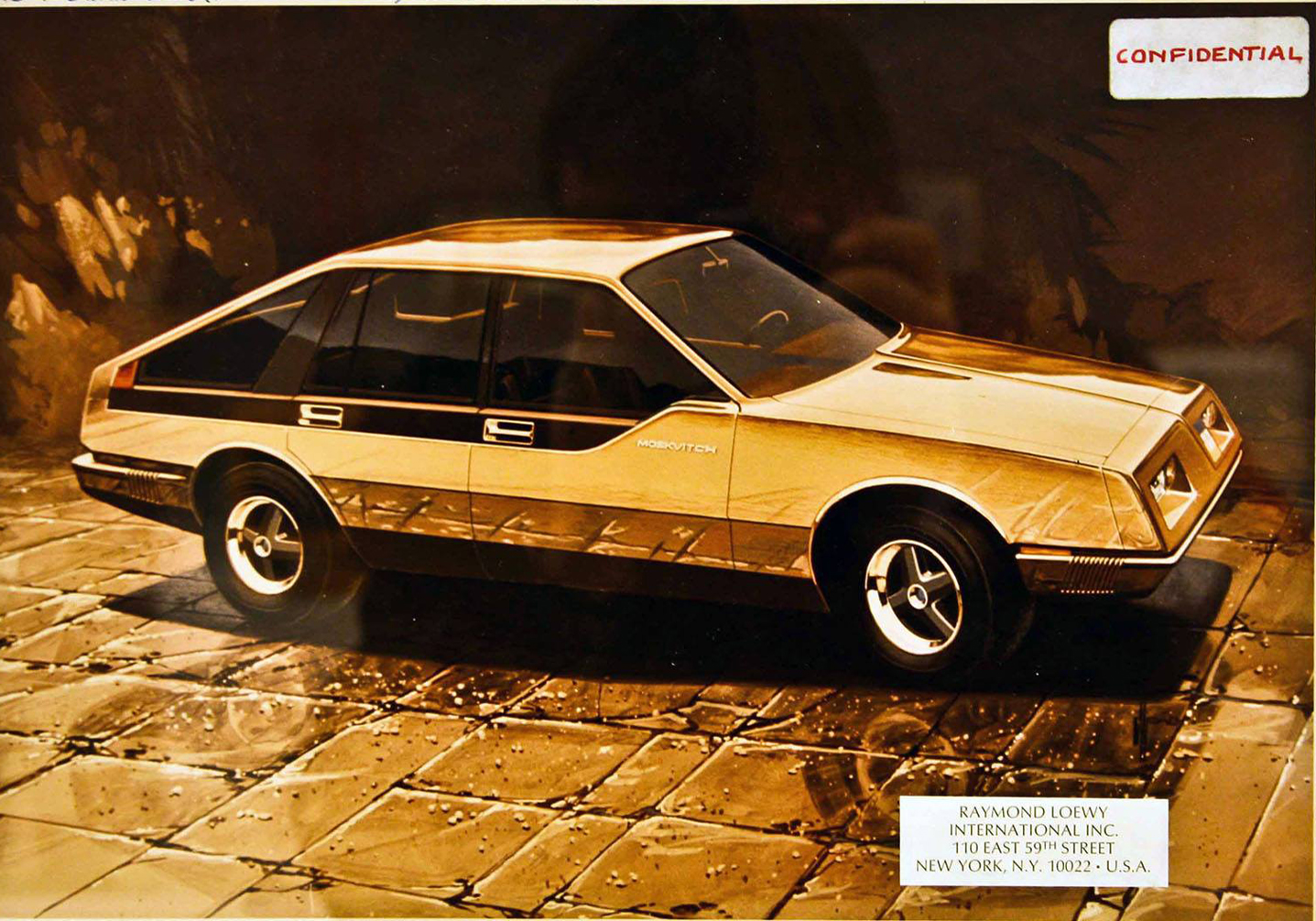

Final Version of Moskvitch XRL

American team members when visiting Moscow had significantly different but equally telling experiences. Never relaxed, team members would purposely leave important looking but useless documents in their hotel trash cans. Conversation outside of buildings enjoyed a significantly different flavor. Inside meeting rooms, positive comments highlighted deadlines being met and schedules moving according to plan. Conversations in open air parks revealed a totally different truth comprised of missed deadlines and poor follow-up. Still, under Loewy’s stern and sharp oversight the Moskvitch XRL concept itself moved on as promised.

Loewy, both confident in and adamant about his vision of the world car his team would create for the Soviets, envisioned the Moskvitch with wide tires and a wide body with flush wheels set out at the corners and a low beltline with a forward slanted body silhouette. However, having provided that direction he said, “Let’s see what the kids have on their mind when given leeway.” Those “kids” were his highly talented team of youthful American designers in their 20s and early 30s all who would speak deferentially of Mr. Loewy throughout their lives.

Loewy, with steely conviction, directed the final concept accented by a color pallet featuring gold and a signature sharp slash at the “A” pillar. Loewy envisioned the driver’s seating position as a cockpit, executed in darker richer leather. In his mind the driver’s seat would be a throne superior to the other seating positions.

While delivery of the completed Moskvitch XRL concept received a warm welcome from the approving Soviets, it coincided with a perfect storm whose winds blew no good for the future of Loewy’s concept.

Moskvitch XRL Interior

As Loewy noted in a discussion of Soviet manufacturing capabilities, “In nucleonics, rocketry, steel plants, and heavy machinery, they do outstanding things. Consumer goods on the contrary are terrible, only fit for a captive market.”

Stated simply, the Soviets did not presently possess the ability to build Loewy’s design. The Loewy team had designed a dream for the Soviets which they were incapable of making. At the same time a new Soviet 5-year plan with a reduced emphasis on foreign markets now held sway. Loewy’s Moskvitch XRL would not be built.

Loewy’s greatest professional achievement proved to be his final professional achievement. Financial problems had surfaced with maintaining such a large operation on multiple continents. By 1977 Raymond Loewy International had filed for bankruptcy.

In retirement Raymond Loewy and his wife Viola moved to France where they continued to live an active life where all was art. Raymond Loewy died in 1986 at the age of 92.

After Loewy’s death two of his former associates wrote in the New York Times saying, “Raymond Loewy altered the look of American life by bringing his streamlined style to nearly every aspect of our lives.”

Loewy at the age of 82 boldly sought to do the same for the Soviet Union. While his designs for the Soviets did not make it to the marketplace, Loewy profoundly advanced the field of industrial design in the Soviet Union by introducing a new language of design and fresh insight into the importance of user-friendly solutions.

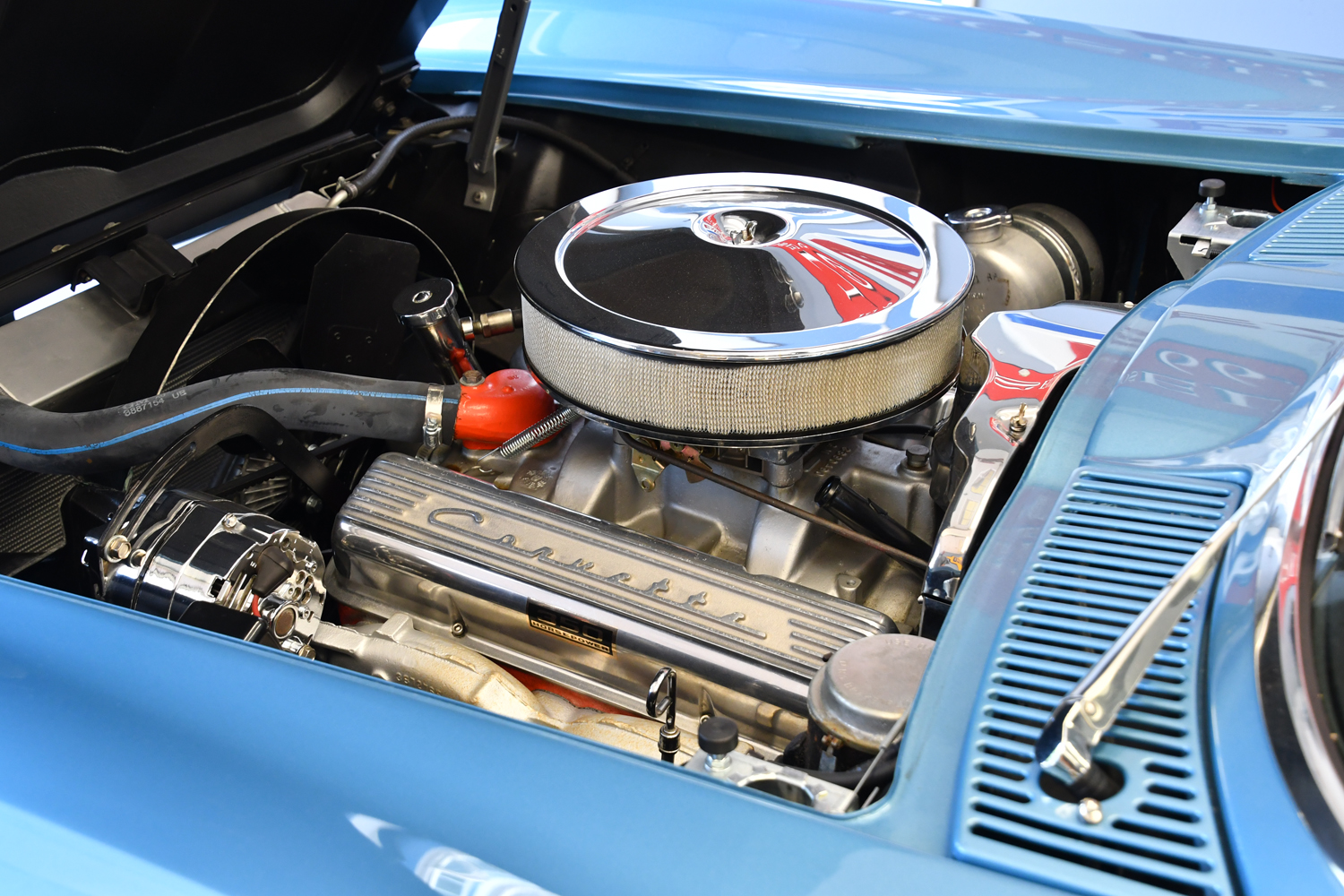

“We do everything except body and paint”,” says Al. Rosell’s Auto Repair eagerly accepts power train and chassis challenges. Al says, “We do new engines, great motors for speed, a wide range of conversions, suspension upgrades, disc brake work, all of that kind of stuff. We also do interior work.” In describing his favorite work Al says, “I love doing engines. We will pull an engine, rebuild it, dyno tune it, detail it and if the customer wants, we incorporate chrome touches to whatever degree desired. When finished, that engine stands out as a work of art that can smoke the tires through all the gears.”

“We do everything except body and paint”,” says Al. Rosell’s Auto Repair eagerly accepts power train and chassis challenges. Al says, “We do new engines, great motors for speed, a wide range of conversions, suspension upgrades, disc brake work, all of that kind of stuff. We also do interior work.” In describing his favorite work Al says, “I love doing engines. We will pull an engine, rebuild it, dyno tune it, detail it and if the customer wants, we incorporate chrome touches to whatever degree desired. When finished, that engine stands out as a work of art that can smoke the tires through all the gears.”

One significant trend that Al has observed over the last few years is the ascendance of the restomod as a preferred choice by many enthusiasts versus the traditional classic car with its original equipment.

One significant trend that Al has observed over the last few years is the ascendance of the restomod as a preferred choice by many enthusiasts versus the traditional classic car with its original equipment. ery interesting cars reside in a special place in Al’s heart. In 2015 an older gentleman approached Al describing a 1966 Corvette that had been in his garage since a bad accident in 1971. Al saw the car. It rested under a deep shroud of dust. Al bought it. He did a complete frame-off restoration. Al says, “Every piece of the car is new except the antenna and the grill. “The Nassau Blue beauty sits proudly in Al’s personal two-bay garage he built on his 4 acres. The other bay holds the subject of a love lost and found.

ery interesting cars reside in a special place in Al’s heart. In 2015 an older gentleman approached Al describing a 1966 Corvette that had been in his garage since a bad accident in 1971. Al saw the car. It rested under a deep shroud of dust. Al bought it. He did a complete frame-off restoration. Al says, “Every piece of the car is new except the antenna and the grill. “The Nassau Blue beauty sits proudly in Al’s personal two-bay garage he built on his 4 acres. The other bay holds the subject of a love lost and found.