Good fortune allowed me to enter the U.S. import car business in the later part of its formative years. For a subsequent period touching 5 decades I had the privilege to write for the vast majority of European automobile brands including, for over 30 years, Mercedes-Benz, Volvo and BMW. It afforded me the opportunity to work with some of the best and brightest professional men and women to grace the import automobile industry. I learned from these experienced, insightful and wise individuals the meaning and importance of “brand.” I admired how they would passionately defend “the Brand.” My time in the business also allowed me to witness corporate decisions that tacked a marque away from their traditional brand values.

This two-part issue of Drivin’ News will ask can “Betraying the Brand be good business?”

Betraying the Brand or Smart Business? Part I

For a product, a brand is a promise. A strong brand adheres faithfully to a set of values highly prized by a targeted market segment. Building a powerful brand image takes time and consistency because building trust takes time (five to ten years is a number quoted) and consistency. A brand that has established a high level of trust usually features a slogan and/or logo, the Mercedes-Benz 3-Pointed Star, Volvo Iron Mark or BMW Roundel that functions as a beacon signaling to targeted customers that this product will fulfill their expectations. A brand that customers have grown to trust represents a hard earned and invaluable asset. A product sending off-brand messages confuses the customer and undermines the brand. It raises questions.

For a product, a brand is a promise. A strong brand adheres faithfully to a set of values highly prized by a targeted market segment. Building a powerful brand image takes time and consistency because building trust takes time (five to ten years is a number quoted) and consistency. A brand that has established a high level of trust usually features a slogan and/or logo, the Mercedes-Benz 3-Pointed Star, Volvo Iron Mark or BMW Roundel that functions as a beacon signaling to targeted customers that this product will fulfill their expectations. A brand that customers have grown to trust represents a hard earned and invaluable asset. A product sending off-brand messages confuses the customer and undermines the brand. It raises questions.

Recently I noticed a new BMW with a redesigned version of the iconic blue, white and black BMW badge. The new iteration called to mind a child’s multi-color swirl lollipop. That together with BMW’s recent addition of the oversized smiling Tasmanian Devil grill gave me pause. I realized that I had witnessed this manifestation of questionable branding efforts before. As a “car guy” such moves always engendered personal doubt and discomfort. As an exercise in retrospection I chose to revisit examples of brand infidelity I had witnessed and dig deeper before I explore two of BMW’s recent curious measures and their potential impact on the BMW brand.

Rather than looking first at BMW, Part I will start on the other side of the Strasse, with BMW’s arch rival Mercedes-Benz and in Part II, Volvo.

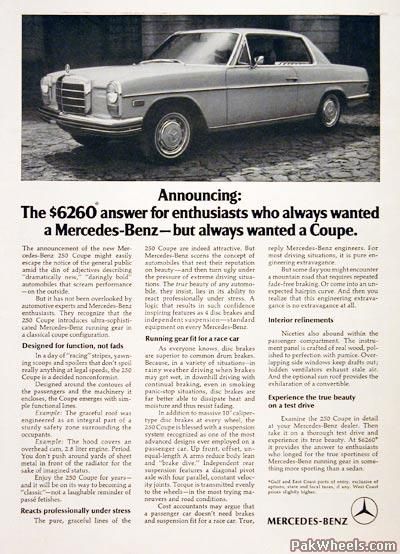

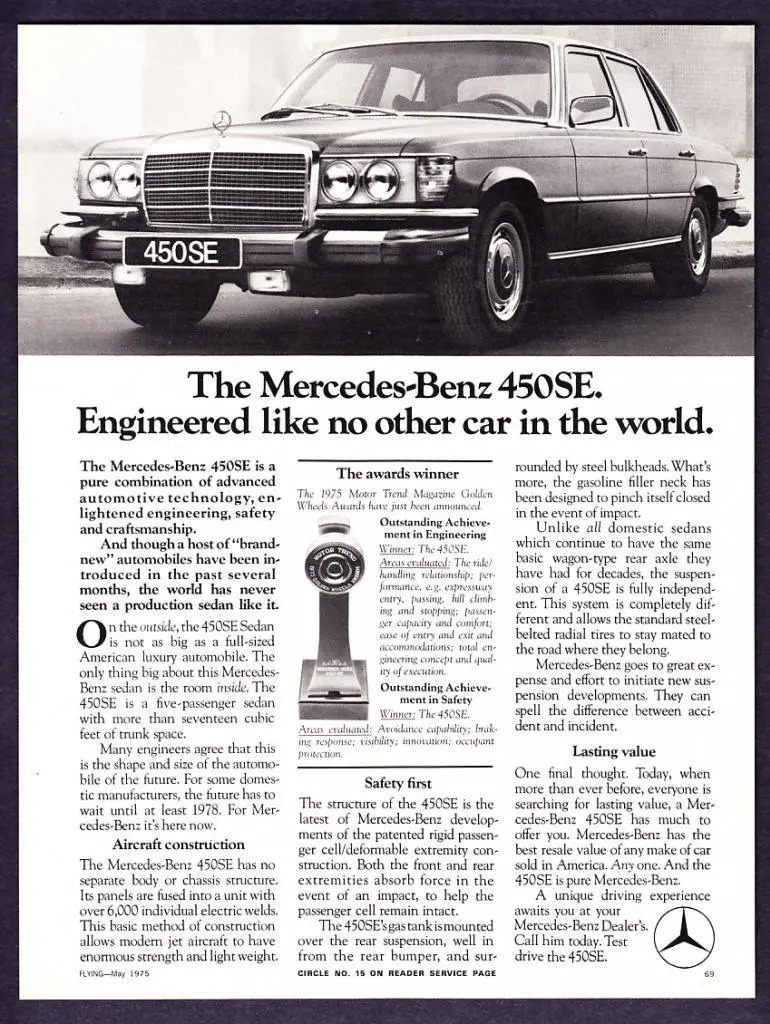

I began working at Mercedes-Benz in 1976. Then, the Mercedes-Benz boldly confident slogan “Engineered like no other car in the world” succinctly captured the Mercedes-Benz commitment to engineering excellence, quality, and luxury. It proudly advanced without equivocation the Mercedes-Benz brand values. As an organizational culture most everyone in the company embraced the passionate self-assessment of Mercedes-Benz as a builder of superior luxury automobiles for customers who understood, respected and could afford superior quality.

In the early years the business plan expressed by Mercedes-Benz management actually considered restricting overall Mercedes-Benz sales to 100,000 units to maintain its limited availability and support premium pricing and healthy margins. It is said that in the 1960s Executive VP of Sales Heinz Waizennegger laughed at the thought that consumers would ever consider paying $10,000 for a new passenger car. By the time I joined, company insiders laughed at the idea of people paying $20,000. By the 1980s nobody laughed any more.

Back then Mercedes-Benz as a company benefited from a workforce populated with skilled and dedicated car guys, both male and female, who, as a group, displayed a quiet and prideful confidence born of their perceived association with an internationally admired, stable and prosperous organization where the employees place and future seemed assured. Gifted engineers and technicians held respected status.

Many employees bought a new Mercedes each year at a favorable discount. Often the following year they would sell their year-old sedan for a profit. For longtime employees the annual profit could build to a cumulative sum where they were buying their annual new Mercedes with what felt like “house money.”

The Mercedes-Benz early North American business model succeeded based on a system where cars were designed, developed and perfected in a timely manner. Much like the aging of a prime steak or the maturing of a fine wine, Mercedes-Benz would bring without great haste well engineered and assorted superior vehicles to a loyal but limited market. However, the late 1980s witnessed U.S. sales volumes and margins declining. Word filtered out of internal management discussions considering the advisability of moving Mercedes-Benz product upscale into higher cost/higher margin but lower volume Rolls-Royce/Bentley territory.

Then Mike Jackson took the helm in 1989. He passionately preached to Stuttgart a message advocating reduced prices with more exciting product and advertising designed to reach a younger and broader market slice. To keep this in context, realize that M-B home office in Germany and M-B North America did not always see eye to eye. In their early years in America the mindset of the predominantly conservative post-war German Mercedes-Benz management in Stuttgart found the North America market baffling and at times infuriating. Especially humorous and emblematic of the disconnect surfaced in the early years when Mercedes-Benz in America pressured Stuttgart for a sunroof as a product feature. The German’s did not see the need when you could simply open the windows but, over time, Germany yielded to the demand. Shortly thereafter America wanted air conditioning. Home office in Stuttgart lost its mind. “The Americans had gotten their sunroof with the fresh air and sunshine now America wanted to close the sunroof and have air conditioning. By the 1980s, however, times were indeed changing with Mercedes-Benz having a more international character.

At the close of 1980s, U.S. sales had dropped for most European luxury car makers, including Mercedes. The economic recession, the luxury tax, and the dollar/mark valuation all played a part in the problem.

A 1991 study by J.D. Powers & Associates found that American luxury owners appreciated prestige but bought reliability, a Japanese brands’ strength. One particular reason for Mercedes’ maintenance issues, as compared to Japanese brands, emanated from Mercedes-Benz emphasis on cars being crafted more than mass produced. The Mercedes-Benz mindset at that time was expressed by Edzard Reuter, then chairman of Daimler-Benz, who said, “We constantly study our position and we always come to the conclusion that we should stay away from mass production. The economies of scale wouldn’t help us. Besides, we have a culture of engineering and product differentiation that would make it difficult.”

However, it had become increasingly apparent that Americans viewed Mercedes’ signature over-engineering as irrelevant. By 1991, Mercedes had started to pay attention to what the American customer and baby boomers in particular, wanted. This sea change in mindset resulted in Mercedes redirecting its focus away from engineering and towards marketing. Germany had listened to Mike Jackson. Mercedes-Benz would respond to a new reality by retaining the 3-pointed star but changing the value proposition it represented.

300SL factory craftsmanship

Like the canary in the coal mine, the slogan “Engineered like no other car in the world” would no longer sing the praises of Mercedes-Benz automobiles. The old brand values buckled under the pressure making way for a new paradigm intent on defining a new path to broader success.

Mercedes-Benz of North America retreated from its engineering-centric heritage to that of a North American marketing function. The retreat created pain. Notorious international business consulting firm McKinsey came in to plan the desired organizational changes with one of the results being a mass layoff of staff members that became known as “Black Tuesday.” This purging of experienced and loyal employees devastated company morale and weakened the foundation of the corporate culture. McKinsey interventions often left such organizational detritus in its wake.

W140 S-Class

The radical departure from past practices would evidence itself when comparing the MY1992 W140 S-Class with its replacement the MY2000 S220 S-Class. With the W140, initial development started in 1981 with it coming to market in 1991. It should be noted that the final product caused much consternation in Germany. The impact of significant cost overruns associated with the project’s over-engineering (Estimate, approx. $1 billion) would ripple through the organization with lasting effects. That said, in the case of the W140, save for a later developing issue with the car’s biodegradable wiring insulation, its excellent build quality and noteworthy expression of over-engineering received wide praise but lukewarm buyer interest. Certainly, new competition contributed to Mercedes’ disappointing sales. Japanese luxury in the form of Lexus and others had burst onto the scene swinging polite but sharp elbows. It forced the staid luxury market including Mercedes-Benz into a period of wrenchingly painful self-examination.

Development of the S220 began in 1992 at the dawn of marketing taking dominance over engineering at Mercedes-Benz. In comparing the S220 replacement for the W140, Motor Trend wrote, “Though hard to pin down, there was something about the S220 that suggested it was developed in an era when the engineers no longer held sway at Mercedes.”

S220 S-Class

Doug Munro, the respected online car reviewer and founder of “Cars and Bids” in comparing the S220 and W140, said, “It represents a low point being the product of cost cutting and simplification in production and engineering.” Munro went on to say, “The earlier goal in producing the W140 was to make the greatest car in the world and they did. In the case of the W220 cost cutting was the name of the game.” The 2000 S500 cost roughly 15% less than the 1992 S500.

So was the Mercedes-Benz course of action that of a brand betrayed or a smart business decision necessitated by a changing market?

The answer may well depend on your point of view. Are you a pure car guy or a business guy? A car guy savors great automobiles built with passion, brilliance, excellence and a cost be damned attitude. Business guys savor a great car that makes money. Car guys love Duesenbergs, Cords, Tuckers, Ferraris, Lamborghinis, Bentleys, Rolls-Royces to name a few. Unfortunately, all went bankrupt or were sold.

As to whether brand betrayal or smart business move, by the year 1998, one would have to say a necessary business decision. Why 1998? Because that year Daimler-Benz swallowed Chrysler and initiated a boiling cauldron of brand confusion and chaos. But that is story for another day.

Did Mercedes-Benz financially benefit from the brand’s redirection? Sales volume would seem to say yes. From Model Year 1991 though 1999 Mercedes-Benz unit sales increased from 58,868 units to 189,437 units. Certainly many factors such as more models, sportier offerings, the competitive set, exchange rates, manufacturing techniques and market conditions impacted sales as well. Furthermore, in considering the earlier fate of pinnacle brands such as Rolls-Royce, Bentley and, later, Mercedes’ own effort with Maybach, the idea of the upmarket move Mercedes-Benz management once considered, would seem to have been destined to fail. Furthermore, based partly on the success of Mercedes-Benz who industry insiders viewed as having been revitalized by Mike Jackson, Jackson now resides in the Automotive Hall of Fame.

In speaking of the old Mercedes-Benz brand, then, it may be best to say, “The king is dead. Long live the king.”

Burton,

Nice article. I would have preferred if M-B stuck with engineering. After all it did serve the company in the past. Maybe customer’s have to be reminded of that value? That’s a messaging issue.

I suspect you are not alone in your thoughts. Thank you.

Great observations here.

Thank you.

Exceptionally concise overview of a very complicated matter: The automotive industry coupled with business decisions while injecting the actual love of the automobile and the care to produce one. Beautiful read, thank you,

As you being a long time and experienced automobile brand guy, your comments are especially meaningful.

very nice job Burton as always, well researched and articulated eloquently ……. expected nothing less from your BRAND

Your comments, as a great writer, are much appreciated.

I worked at a very large dealership that had Mercedes, BMW and Lexus all on display in one location. This was in 1989, When the Lexus brand arrived on scene. I used to chuckle when a German brand owner looked at the estimate for a simple tune up or minor repair. Like their hair was on fire. Can’t count the number of them that would literally run to our Lexus showroom and say “Please get me out of this thing “ ! The Japanese had studied well the plight of the vaunted German owner experience.

Sounds like excellent on site reporting from the scene of the crime.

Fascinating! I can’t wait for the next entries in this series…

Thank you. It’s coming soon.