So it’s late summer of 1977. A bright eyed blonde haired young man just out of his teens with a gift for things automotive had become known for his accomplishments while working with his father restoring vintage Jaguars. One afternoon a customer approached him mentioning knowledge of a Ferrari being prepped for IMSA class endurance racing. He asked if the young man would be interested in interviewing for the team? With his father’s blessings, young Bryan Maletsky left work at closing and headed off to meet the Ferrari 512 Berlinetta Boxer (512BB) that would ultimately bring him to the 24-hours of LeMans in 1978.

LeMans 1978, a young man’s memories

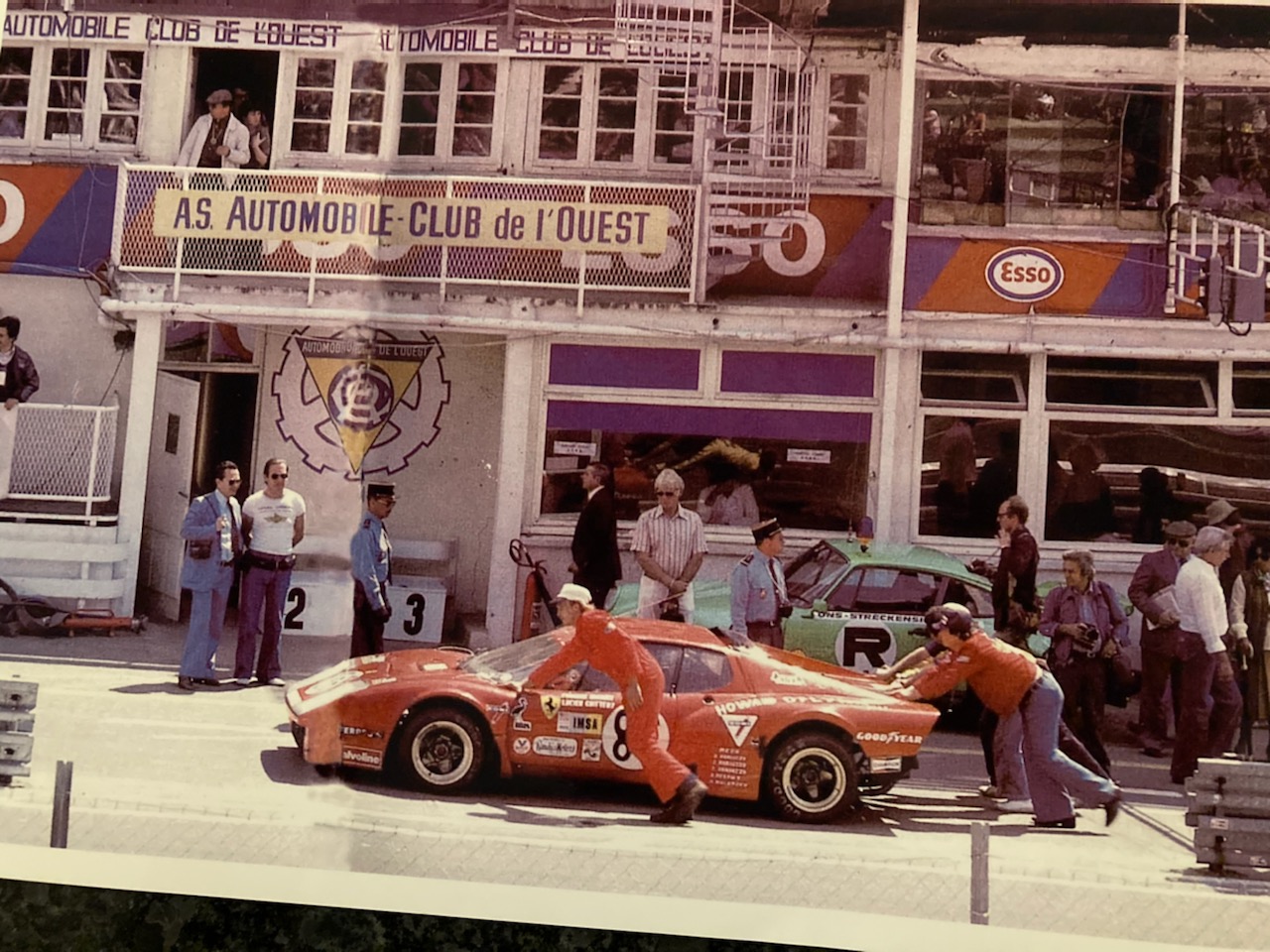

Bringing the Ferrari to the starting grid

Bryan Maletsky entered the workshop of Randy’s Motors in Clifton, New Jersey. Surrounded by the Ferraris, Maseratis and Lamborghinis in which Randy’s Motors specialized, Bryan arrived to meet the IMSA class Ferrari’s Chief Mechanic, Randy Randazzo, owner of Randy’s Motors.

After Bryan acknowledged to Randy that he had little experience on Ferraris but had considerable electrical troubleshooting experience Randy said, “Good, you can start tonight. Let’s see how you do.” “Do what?” asked Bryan. He was directed to rewire the Berlinetta Boxer’s instruments and dashboard, put in new connections and correct all the wiring that had been improperly done previously, re-solder all the connections and secure all the wires. At the end of the night Bryan had earned Randy’s respect and a place on the racing team.

Randy’s 512BB began life as a NART (North American Racing Team) car built and campaigned across America by famed Chinetti Motors for the 1975 and 1976 seasons.

Acquired from Chinetti in 1977 by new owner Howard O’Flynn the 512BB shipped from Connecticut to Randy’s where the car would be prepped for the 1978 season with hope but no guarantee of going to LeMans.

As a new team member Bryan’s days filled up quickly. Still committed to supporting his father’s East Rutherford, New Jersey Jaguar restoration business Bryan would leave there around 5:30 and head straight to Randy’s where the team worked into the wee hours of the morning focused on getting the Ferrari sorted out and ready for the 1978 IMSA endurance race season.

Born to run and bred to run fast, this 512 BB got life from a seriously worked 5-liter, flat 12-cylinder with 12 Webers. It far exceeded the stock 340 horsepower delivered through the 5-speed manual transmission.

“Swiss cheesed” rear panel

Running fast not only meant adding power but equally critical it demanded losing weight. Weight reduction meant anything that did not contribute to structural integrity or performance would be lightened or removed. With the interior already gutted, attention turned to any flat piece of steel that had no structural purpose. It would immediately be “swiss cheesed” using an array of different size hole saws to remove as much metal as possible. The lightening process got down to stripping paint from any part that did not need to be painted. It got to the point where any bolt that extended needlessly far past the nut would be replaced with a shorter bolt. Lightening efforts resulted in a weight reduction of 70 Kg.

With the Ferrari ready and the season upon them, the O’Flynn team faced an IMSA endurance race schedule that included Daytona, Watkins Glen, Road Atlanta and Talladega. Now, late nights would be spent making the car ready for each subsequent race.

The road to LeMans for a prospective competitor must be paved with high levels of competitive performance at major endurance races. The O’Flynn Berlinetta Boxer proved its mettle on the track and earned an invitation to LeMans. The car was going and So was Bryan.

The invitation put all hands on deck and all things in crates. As Bryan recalls, “Tool chests, tools, no matter what you thought you had was enough, it was always doubled or tripled.” All needs, every contingency had to be accounted for.”

Then in what Bryan says, “Felt like a blink,” the prepped Ferrari, parts, tools and team found themselves high over the Atlantic headed for touchdown at La Sarthe the small regional airport convenient to LeMans.

Bryan Maletsky at driver’s door pushing 512BB to starting grid

With the Ferrari on a separate plane the team focused on getting to their accommodations. They would be staying at the home of lead driver Francois Migault’s parents. Work on the car would be performed at a local Renault dealership.

For Bryan and the rest of the team, hitting the ground sent them into a whirlwind of car support activity that would not subside for the coming week and half right through race day.

Bryan says, “We really didn’t even have time to think about the race except to make sure that the car benefitted from everything being done and done properly.” “By properly” means that every nut and bolt tightened would be marked with the specific personal color identifying the team member who secured the nut, bolt or fitting.

In preparing the car, a serious problem arose when lead driver Migault took the Ferrari out on a local airfield to shake the car down and run it at some race level speeds.

When Migault pulled in and exited the car after a number of runs, he clearly lacked enthusiasm for the 512BB’s engine’s ability to deliver the goods. He felt the engine, one of three the team had brought, could not deliver the power needed to be competitive. Interestingly this engine had been provided by Ferrari in Italy. Acting to rectify the problem the team swapped out the Ferrari built engine to be replaced with the engine that had been prepped back in the States at Randy’s. After some serious testing, Migault returned to announce that this engine had the guts to chase the glory.

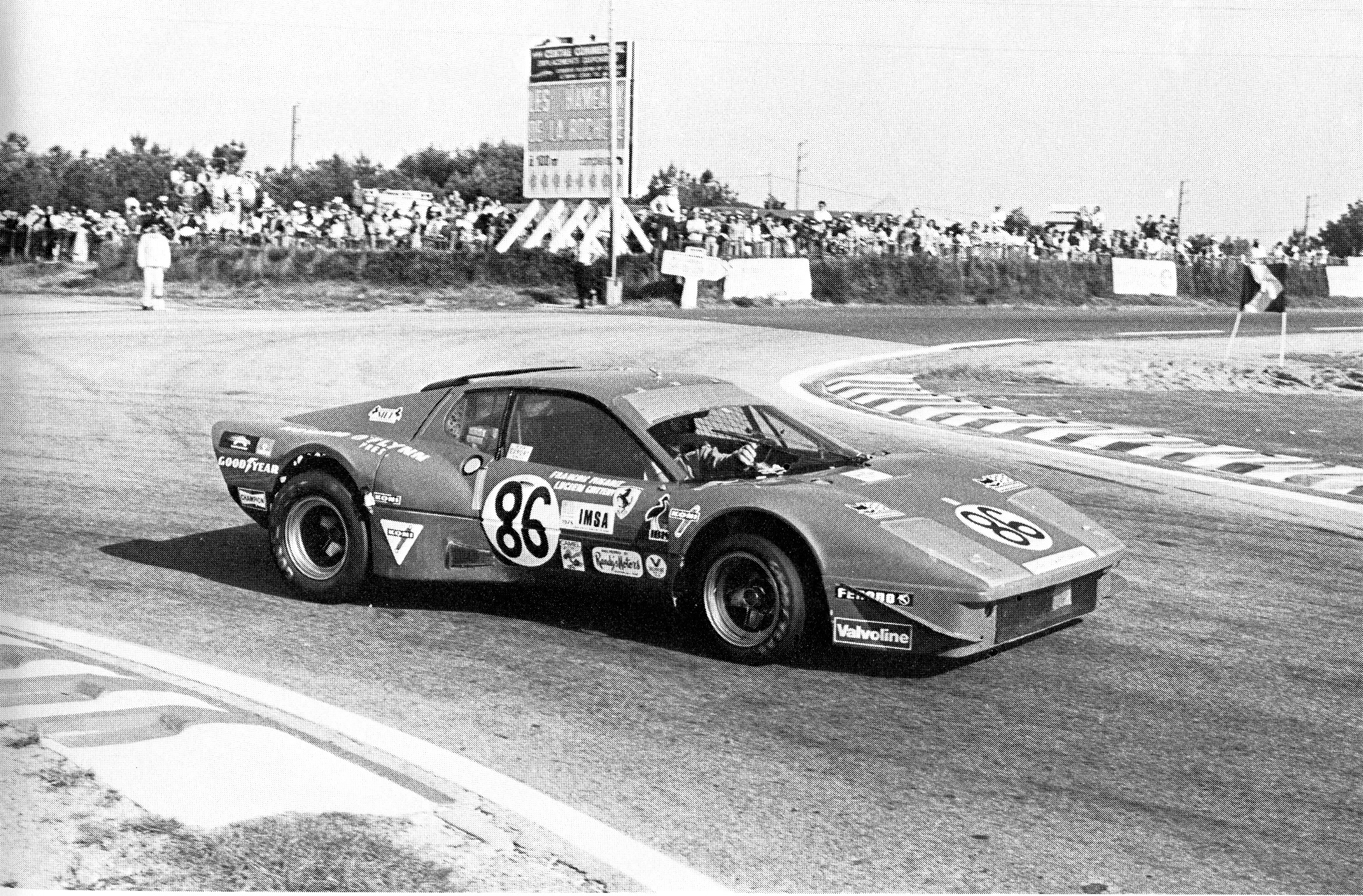

The 512BB running at Daytona

While Bryan’s lack of French fluency for the most part served as a hindrance, it did offer a few key benefits particularly during questioning by the scrutineers (French judges who determined if a car complied with all rules and requirements). Anything that the team did not want discussed became a troublesome language issue that would frustrate the French officials to the point that it would usually result in the judges simply walking away.

As well, a little theatrics came to the rescue when the team realized that their rear end body dimensions fractionally exceeded the width limit. As the scrutineers approached, Bryan got into a boisterous shouting match with a fellow team member. French officials wanted nothing to do with the crazy Americans and simply walked on by. Disqualification averted.

At last, race day arrived bringing a confluence of spectacular cars, world class drivers, iconic signage, thunderous engine noise, screaming crowds and the pungent smells of high octane auto racing in the air. Drivers for the O’Flynn team would be Francois Migault and Lucien Guitteny. Bryan says, For me it was an event of a lifetime.”

Strong and nimble the 512BB attacked the course. It effortlessly clocked over 200 mph on the Mulsanne straight. Tire swapping played an important role in a strategy designed to promote the survival of the car to the end of the race. Taller tires would provide a higher top end. Shorter tires would provide quicker acceleration. So depending on day or night and the car’s position in the race tire choice played a major role.

Disaster would strike midway through the race when the Ferrari’s driveshaft broke away from the pits. When a car breaks and does not make it to the pits, LeMans rules demand that any repair must be performed by the driver. The only thing a team mechanic can provide is verbal direction. With a replacement driveshaft in hand a team member took a service road out to the broken Ferrari’s location and stood by the driver providing point by point instruction which Driver Guitteny carried out flawlessly.

With no further problems destined to occur, the Ferrari roared back to complete the race third in class and 16th overall. No Ferrari finished higher in the standings. Actually no other Ferrari, factory sponsored or otherwise, even finished the race.

To the nationalistic displeasure of some competing European teams, Bryan and his team members draped an American flag on the car as they toured the track.

In reflecting on the experience 40 plus years later, Bryan says, “Simply to be part of that international racing experience was an honor and then to be competing and finishing? Oh my God. That we finished, made us feel like we won the race.”