Roads We Remember #3

As cultural icons, certain local roadside features past and present possess a mythic life of their own. Over the course of our lives they become universal reference points integrated into our personal story.

The “Evil Clown” of Middletown, NJ and the Red Apple Rest in Tuxedo, NY are two. Without doubt, high on that list resides the Indian Motorcycle sign of Palisades, NY.

Mystery of the vanishing

Indian Motorcycle sign

Hugging Route 9W North on the New Jersey side of the Hudson, the 9W Market offers a  gourmet food oasis that has become a magnet for bicyclists from all over the Tri-state area. It is doubtful that anyone enjoying their pan fried organic egg sandwich has a clue about the structure’s first life and its starring role in one of the boldest automobilia thefts in local history.

gourmet food oasis that has become a magnet for bicyclists from all over the Tri-state area. It is doubtful that anyone enjoying their pan fried organic egg sandwich has a clue about the structure’s first life and its starring role in one of the boldest automobilia thefts in local history.

Even from my early boyhood viewpoint in the back seat of my family’s 1948 Chevy Fleetline Aerosedan, our Sunday drives north on Route 9W never failed to entertain. Craning my neck like a hungry hatchling to peer out the small teardrop rear window, I loved the old roadhouse bars that seemed to defy gravity as they clung to the steep face of the great Palisades. For me though, I derived special delight from the old homey gas stations as they appeared through my back seat porthole.

Of all the wonders of roadside Americana that my family Sunday drives afforded, none gave me greater joy than a weathered white Gulf station with a snack bar. Like the little engine that could, it stood proud and alone in its diminutive glory each time we motored by, and we always motored by because my father only used Sunoco gas.

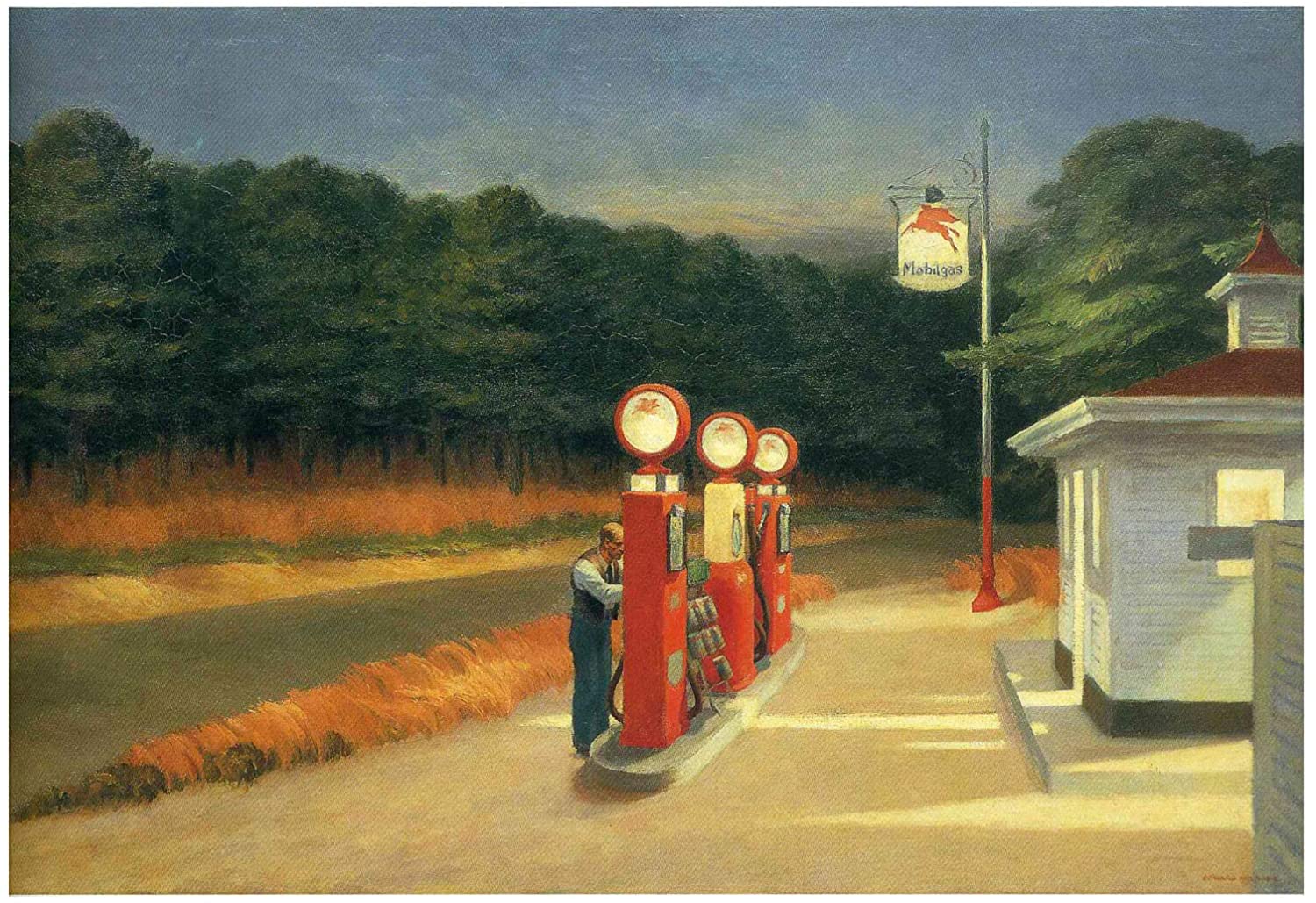

Years later I learned that the little Gulf station enjoyed another admirer in the person of iconic American artist Edward Hopper. Born and raised in nearby Nyack, New York, Hopper is said to have drawn inspiration from the little station for his iconic 1940 work “Gas”.

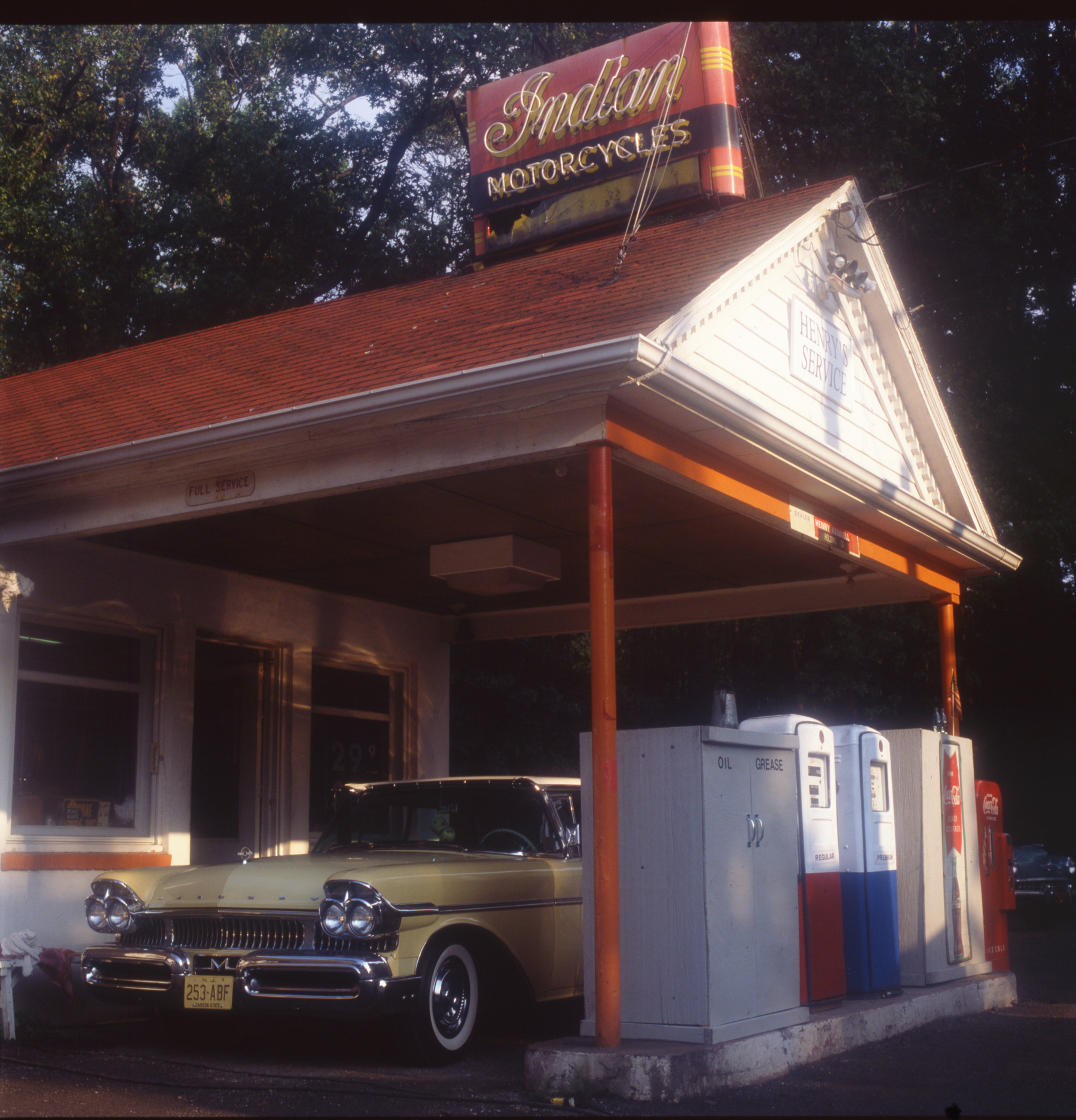

The little Gulf station began life in 1939, when a towering rawboned motorcycle enthusiast named Henry Kennell built it as a sales point for Indian Motorcycles.

Time passed in decades. The world around Henry’s Gulf morphed into the frenetic Tri-state area. However, Henry’s Gulf remained a constant and his section of 9W seemed content to linger in 1939. One part of Henry’s Gulf though, while remaining unchanged, did steadily grow as an object of desire. Firmly affixed to the ridge of Henry’s station sat perched the crown jewel of Henry’s Gulf. There reigned the king of all signs, a roughly five foot by three foot glorious two-sided neon masterpiece that in 1939 proclaimed that beneath it could be found a genuine Indian Motorcycle dealership.

I met Henry in 1989 when I negotiated with him to film a Volvo Finance commercial set in 1961 at his, then, still active Gulf station.

Henry Kennel in spite of his 92 years maintained a gentle giant countenance. Warmly greeting you by extending a massive hand, the firm handshake seemed to extend past your hand and carry up to your elbow. His kind and affable manner like his Gulf station made you feel welcome.

From time to time during filming of the commercial Henry would saunter over from his house across Route 9W. During the breaks he would respond to my urgings to share some history of his station. He knew his Indian sign was special and he loved it.

Henry’s sign constantly generated inquiries.

Interest would often come from members of a motorcycle group called “The Sons of Danger.” A gregarious and fun loving collection of serious motorcycle enthusiasts, “The Sons of Danger” originated in the 1970’s as a creation of two pillars of the automobile advertising community. Its membership included executives of numerous automobile companies, journalists, and drivers. Names like Dan Gurney, Brock Yates and Paul Newman populated its roster.

Since the North American headquarters of Volvo resided barely a few miles away, “Sons of Danger” members including one of the two founders were keenly aware of Henry’s glorious sign. Many offers were made. Henry would not budge. Years turned to decades all the while the great Indian sign proudly anchored the present to the past from its position on high.

In 1991 Henry Kennell passed away. In a fitting continuation of ownership by kindred spirits, Henry’s Gulf station would be purchased by a legendary local vintage car owner and supplier of vehicles to the film industry, Jerry McSpirit. Owner of Cars of Yesterday Sales and Rentals, McSpirit’s involvement in supplying vintage vehicles to the film industry dates back to 1970. He provided a vehicle for my film shoot in 1989.

During McSpirit’s ownership much stayed the same. Certainly the Indian sign maintained its exalted and coveted status.

“An ill wind blows no good” goes the  adage. For Jerry McSpirit Tropical Storm Floyd in 1999 fits the bill.

adage. For Jerry McSpirit Tropical Storm Floyd in 1999 fits the bill.

Beginning as a Category 4 hurricane in the Bahamas, Floyd was a tropical storm by the time it reached northern New Jersey. The tropical storm packed punishing torrents of rain. September 16th 1999 witnessed record flooding and Dams bursting across New Jersey. It also marked the last time Henry Kennell’s Indian Motorcycle sign was ever seen.

When McSpirit went to assess the storms impact on his little station, the only damage to be seen was where the Indian Motorcycle sign had been carefully removed. During one of the worst storms in New Jersey history and after 60 years in place, Henry Kennell’s treasured Indian sign disappeared.

Jerry McSpirit sold the little Gulf station shortly thereafter.

Despite the offer of a generous reward, the last 21 years has not produced one word as to the fate of Henry Kennell’s Indian Motorcycle sign.

dreams thanks to Papa Santucci’s prolific storytelling abilities and great friendship with Dagavar. Rich with grit, bravado, exotic cars and famous drivers, stories about Dagavar racing his Jaguar filled the Santucci’s Bronx kitchen and gave substance to a child’s dreams of adventure.

dreams thanks to Papa Santucci’s prolific storytelling abilities and great friendship with Dagavar. Rich with grit, bravado, exotic cars and famous drivers, stories about Dagavar racing his Jaguar filled the Santucci’s Bronx kitchen and gave substance to a child’s dreams of adventure. Having dueled against a pantheon of driving legends such as Briggs Cunningham, Stirling Moss, Luigi Chinetti, Phil Hill, Carroll Shelby and Mike Hawthorne; it was only fitting that Dagavar’s Jaguar, in an age of trailer queens, would benefit from Santucci’s passionate desire for the Jaguar to run strong and free.

Having dueled against a pantheon of driving legends such as Briggs Cunningham, Stirling Moss, Luigi Chinetti, Phil Hill, Carroll Shelby and Mike Hawthorne; it was only fitting that Dagavar’s Jaguar, in an age of trailer queens, would benefit from Santucci’s passionate desire for the Jaguar to run strong and free. In the course of multiple exchanges, Strader, put Santucci in touch with Roger Payne of Perth, Australia. Payne a retired engineer and Jaguar historian was a fountain of Jaguar information.

In the course of multiple exchanges, Strader, put Santucci in touch with Roger Payne of Perth, Australia. Payne a retired engineer and Jaguar historian was a fountain of Jaguar information. cial sauce that enticed the Greenwich Concours d’Elegance to invite the Dagavar Jaguar to display on Sunday June 2nd 2019.

cial sauce that enticed the Greenwich Concours d’Elegance to invite the Dagavar Jaguar to display on Sunday June 2nd 2019.

themed designer cutlery and place settings. Proper social distancing is no problem. There is only room for two.

themed designer cutlery and place settings. Proper social distancing is no problem. There is only room for two. All the restaurants visited functioned with an almost military precision. Cell phones alerted customers to pull up as the food came from the kitchen. Payment was either done by card in advance or with mobile hand units at pickup.

All the restaurants visited functioned with an almost military precision. Cell phones alerted customers to pull up as the food came from the kitchen. Payment was either done by card in advance or with mobile hand units at pickup. We are at a fraction of our normal business but we are holding on. I miss the people. I am so thankful that I am going to be allowed to have some seating on June 15th though it will only be half capacity. Before Covid-19 It was already hard to make a living in the restaurant business so TAKE OUT will remain critical to our survival.

We are at a fraction of our normal business but we are holding on. I miss the people. I am so thankful that I am going to be allowed to have some seating on June 15th though it will only be half capacity. Before Covid-19 It was already hard to make a living in the restaurant business so TAKE OUT will remain critical to our survival. have owned Peppercorn’s for a year. I never saw this coming. They say tough times make you tougher. So be it. Right now if it wasn’t for TAKE-OUT I would have my doors shut.

have owned Peppercorn’s for a year. I never saw this coming. They say tough times make you tougher. So be it. Right now if it wasn’t for TAKE-OUT I would have my doors shut. we bridge to the future “new normal.” Opening up outside is going to help. We are planning for inside where we will have socially distanced seating. If we are lucky we will be doing maybe half of what we used to do. TAKE-OUT will remain fundamental to our continued existence.

we bridge to the future “new normal.” Opening up outside is going to help. We are planning for inside where we will have socially distanced seating. If we are lucky we will be doing maybe half of what we used to do. TAKE-OUT will remain fundamental to our continued existence.

for one year.

for one year.

in a lower gear. Once finding that low gear RPM sweet spot, the engine‘s throaty exhaust note will be enriched and reverberated by the sheer stone face of the Palisades that flanks the road. This rumbling symphony enhances the sensory delight courtesy of the Henry Hudson Drive, a narrow serpentine road clinging to the towering Palisades. Driven at night only makes it better.

in a lower gear. Once finding that low gear RPM sweet spot, the engine‘s throaty exhaust note will be enriched and reverberated by the sheer stone face of the Palisades that flanks the road. This rumbling symphony enhances the sensory delight courtesy of the Henry Hudson Drive, a narrow serpentine road clinging to the towering Palisades. Driven at night only makes it better. however, the Hudson Valley is actually the southernmost fjord in the northern hemisphere.

however, the Hudson Valley is actually the southernmost fjord in the northern hemisphere.

be seen on the street and Mary Pickford made her film debut. It would last but a decade as bitter winters and cheap land in balmy southern California put a quick end to New Jersey’s silver screen dreams.

be seen on the street and Mary Pickford made her film debut. It would last but a decade as bitter winters and cheap land in balmy southern California put a quick end to New Jersey’s silver screen dreams.